What to know about ‘white labelling’, the beauty industry’s open secret

WORDS BY DAISY HENRY

What exactly is a white label beauty product?

Like many people, my bathroom beauty cabinet is stocked with dozens of brands. My skincare routine, for example, starts with one type of cleanser, another brand’s toner, a different company’s serum and then a completely different moisturiser. And let’s not get started on makeup. I’d like to think I’m fairly discerning about the brands I choose – largely due to a combination of reviews, my own skin concerns and affordability.

But truthfully, I’ve given little thought to how these products have made their way to my bathroom. Perhaps naively, I’d assumed that for each brand, the founders were tinkering away in their own in-house beauty labs, concocting new formulas. But this isn’t typically the case.

For more beauty news, guides and reviews, head to our Beauty section.

I came across the concept of ‘white labelling’ after reading commentary on an article from the Australian Financial Review (AFR) chronicling the controversies surrounding Australian skincare label, Ultra Violette. Much of the discourse centred on one key sentence written about the brand’s product, Lean Screen. “The fundamental formulation of Lean Screen is not even proprietary to Ultra Violette,” it reads.

Truthfully, I had no idea what this meant at first glance, but after research and interviews for this story, I’m able to translate. Effectively, a formula is proprietary to a brand if the company owns or holds exclusive rights to it. If a formula’s not proprietary to a brand, the manufacturer might instead own the formula and choose to sell it to multiple parties.

In the case of Ultra Violette, the AFR reports its Lean Screen formula includes additions that make the final product unique to the brand, such as Kakadu plum and pentavin. What the publication didn’t report is that Lean Screen is one of the only formulations in the Ultra Violette range that is manufacturer-owned.

In a comment to Fashion Journal, an Ultra Violette representative noted, “All other facial Skinscreen formulations in our range are our own and have been developed by our in-house product development team which consists of four people (including a cosmetic chemist and regulatory expert) and led by co-founders Ava Matthews and Bec Jefferd, who are also both product developers at heart.”

All of this got me thinking: How many beauty brands are using non-proprietary formulas, and what exactly does this mean for our skincare routines?

What is ‘white labelling’ and how is it different from ‘private labelling’?

White and private labelling are both longstanding practices in the beauty industry. In essence, white labelling occurs when one company (often a manufacturer) creates a product and a different company (often a brand) sells it as their own, without exclusive rights or ownership.

One of these manufacturers is Greenleaf Cosmetics Australia. Having spent over 20 years in the manufacturing industry across Australia, Asia and Europe, founder and managing director Mamun Haque created Greenleaf Cosmetics in 2018, with the vision of producing environmentally conscious beauty and lifestyle products.

Mamun defines white labelling more eloquently. “In the context of cosmetics and personal care, [white labelling] means a manufacturer like Greenleaf Cosmetics creates high-quality products, such as serums, lotions or shampoos, that are then packaged and sold under another brand’s name,” he explains. “The end consumer sees only the branding of the selling company, not the manufacturer.”

This approach means that brands can launch products quickly without investing in the testing, formulation, production or compliance requirements for themselves. “It’s a smart solution for businesses that want to focus on marketing, retail or e-commerce while relying on a trusted expert for manufacturing,” he tells me.

Erika Geraerts, founder of Fluff cosmetics, Melbourne-based beauty brand, known for its refillable lip, bronzing and blush cloud compacts, agrees. She notes it’s fairly rare for beauty brand founders to have a background in chemistry. “More often than not, they come from a marketing background or represent a consumer pain point,” she says.

According to Erika, the costs of exclusively holding the IP rights to a formulation can be prohibitive for small and emerging businesses, which goes some way to explaining why many beauty brands start with non-proprietary formulas.

“With the influx of brands on our mass market, there’s little room for product innovation,” she says. “What this means is that we’re seeing very similar base formulas that have been refined and developed by brands based on founder preferences, consumer insights and market trends. And there’s nothing wrong with this.”

This approach, where brands customise their products, creating bespoke formulas and recipes, or tweaking existing formulas, is a variation of white labelling, known as ‘private labelling’. Though both white and private labelling rely on a third party to manufacture products, private label products are often tailored and exclusive to one brand.

All this doesn’t mean Australian beauty brands have stopped developing original formulas independently, but given the steep costs involved, Erika says very few are able to.

View this post on Instagram

How common is white and private labelling in the beauty sector in Australia?

From Mamun’s perspective, it’s a fairly common and well-established practice. “To my best knowledge, there are more than a thousand contract manufacturing companies in Australia offering white label personal care products,” he tells me.

Fluff also works closely with a manufacturer to develop its lip oils, bronzers and blushes. “We work with a local Australian skincare manufacturer who has developed our formulas based off a few natural oil inclusions,” Erika says. “For our makeup, I spent three years sampling with various manufacturers both locally and internationally, working with our desired ingredient lists, product payoffs and understandings of foundational makeup formulations.”

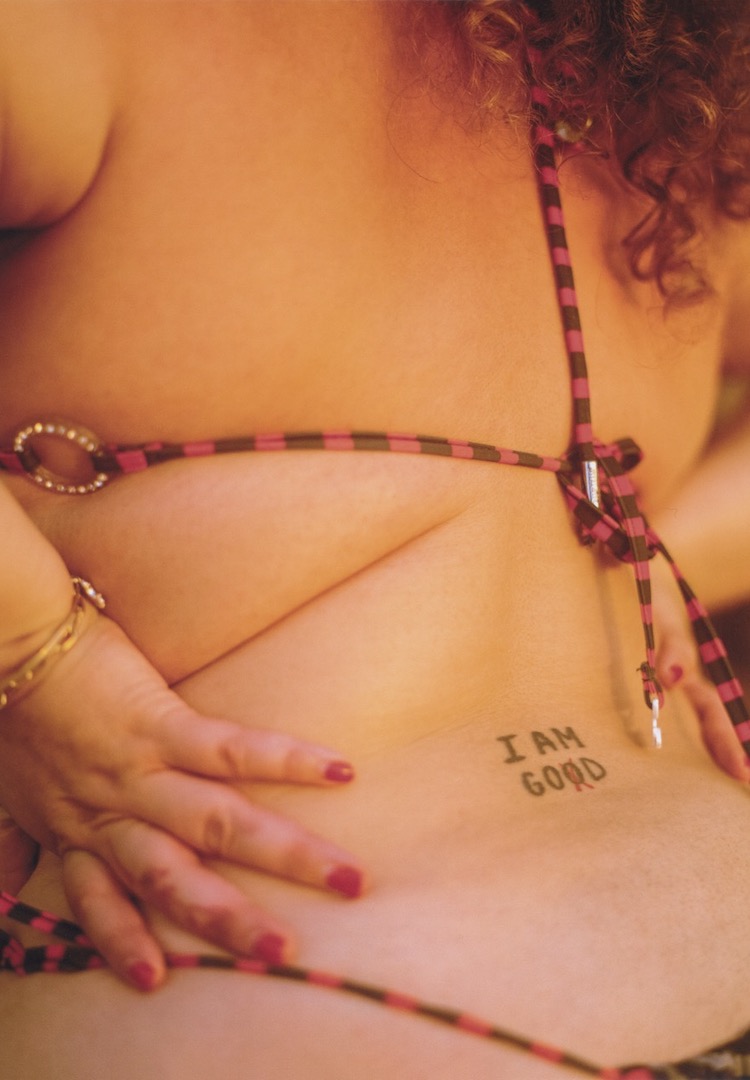

“We don’t claim that our makeup is revolutionary or reinventing the formulation wheel but rather, it’s a reliable formulation for people who want a simpler, natural approach to how their makeup looks and feels.” For Fluff, its refillable packaging and approach to beauty consumption (that has led to the creation of its Substack, Issues, and podcast, Pretty Hard) is just as important, and helps set Fluff apart from competitors.

Is ‘white labelling’ a bad thing?

Not in practice. If a brand is launching a new product, Mamum says white labelling can be a smart and scalable solution. The benefits of this approach include that beauty brands can get their products to market quickly and efficiently, while focusing on branding and customer experience.

“However, like any business decision, it comes with trade-offs,” Mamum says. For example, it means brands have limited formulation control, a dependence on third parties and potential challenges in differentiating their product from others.

“The [downside] is that you can’t claim it’s unique to your brand, which many still do,” Erika adds. “And just as you have done, another brand or business can use your formulation.”

Yet as the founder of Fluff, Erika’s background and expertise lies in marketing, not in crafting formulas from scratch. “My personal philosophy around skincare and makeup is quite simple and grounded in natural ingredients. However, our consumer, and the wider industry, demands a product that has shelf life and performs to their expectations,” she says.

It’s not a one-fits-all solution, by any means. But for those who do face barriers to entry, or don’t have the means to ensure their product can be fully and safely tested and regulated, white and private labelling is a clear solution.

This article was amended on July 23 to include clarifications and commentary from Ultra Violette.

For more on beauty product formulations, try this.