Exposure Therapy: What does a ‘revealing’ outfit mean these days?

WORDS BY SIENNA BARTON

COLLAGE BY SIMONE ESTERHUIZEN

“I personally find owning my own objectification – and using clothes as a way of reclaiming my visual identity – to be both powerful and healing.”

A revealing outfit can make or break a woman’s career. As someone who grew up in the early 2000s, my understanding of what’s seen as ‘revealing’ or ‘appropriate’ is quite warped. When Kate Moss, Gwyneth Paltrow and Nicole Kidman wore sheer dresses on the red carpet, it was deemed chic.

Around the same time, Janet Jackson performed at the 2004 Super Bowl, where Justin Timberlake famously ripped off part of her bustier, revealing a jewellery-adorned nipple on live television. Her decades-long career was tainted and has never truly recovered.

For more fashion news, shoots, articles and features, head to our Fashion section.

Over 20 years on from the nipple debacle, there’s still a double standard when it comes to nudity in public arenas. Primed by a culture that tells us any publicity is good publicity, stunt dressing has only become more prevalent, and the reactions to it more divided. In the days that followed Bianca Censori’s coat-drop moment on the 2025 Grammys red carpet, revealing a completely transparent dress with no underwear, the internet was abuzz.

Many social media pundits saw her outfit – a Yeezy creation aptly named ‘The Invisible Dress’ – as exploitative, speculating that the notably silent Censori was simply serving as her husband’s accessory. Some theorised the stunt was part of an elaborate, humiliation kink, with Ye getting off on his wife being publicly debased. Others lauded her for #freeingthenipple, while an angry chorus of concerned citizens bemoaned a woman baring her body in its entirety on the world’s stage.

In an opinion piece for The Conversation, Senior Lecturer at RMIT, Harriette Richards, explores how fashion statements like Censori’s dress prompt conversations about misogyny and the policing of women’s bodies. “Some previous instances of naked dressing have been cause for celebration. They seem to have symbolised a feminist victory, indicating the power of women to take control of their appearance and their bodies,” she writes. Some but not all. When the only bodies on show are thin and meticulously manicured, is it really a victory?

The art of the tease

A core criticism of Censori’s dress was that it left nothing to the imagination. There was no ‘nude illusion’, just nude. Our cultural obsession with near-nakedness can be chalked up to the ‘Theiss Titillation Theory’.

Named after American costume designer William Ware Theiss, it speculates that a person’s (usually a woman, let’s be honest) proximity to nakedness allows for the viewer (usually a man) to fantasise about the possibility of clothing falling off. In other words, the anticipation of what’s underneath a lacy bra or a low-cut dress is somehow sexier than nakedness itself.

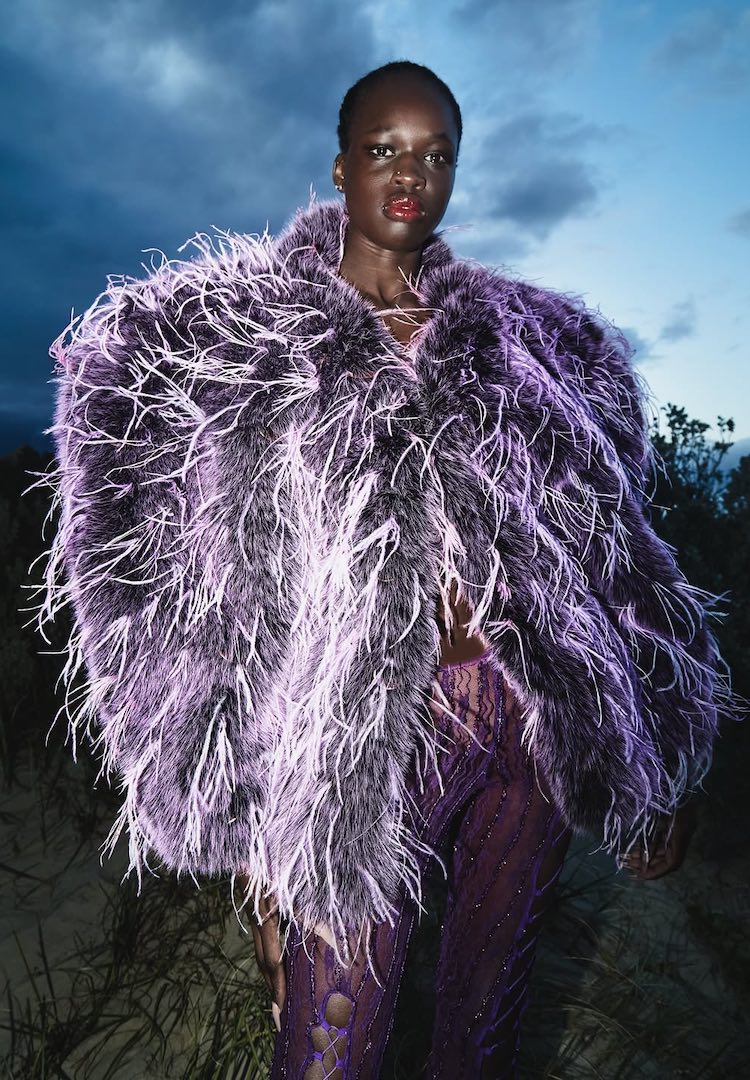

Baring skin is nothing new, but fashion labels have become more creative in finding these ‘gaps’ to showcase. While we’ve seen different variations on cleavage, sideboob and underboob, many Australian designers are experimenting with sheer styles and cut-outs to expose the unexpected.

Take Christopher Esber’s signature gowns that reveal puzzle pieces of skin, Ramp Tramp Tramp Stamp’s ‘logo removal’ T-shirts that frame a window of chest just above the cleavage, Kahe’s jeans with cut-out slices at the hips, or Catholic Guilt’s bespoke chainmail piece worn by Julia Fox at the NGV Gala, complete (or, incomplete) with a butt-baring cut-out.

Designer Ella Jackson of Catholic Guilt says she liked the juxtaposition of having a material traditionally used as armour against bare flesh. “It feels vulnerable, having that much skin on display, but something about using steel and stones as a material makes it feel a bit tougher and punk, and like a bit of a middle finger to modern-day societal norms.”

Not every body

There’s a lot of fun to be had with risqué sheer clothing and creative cut-outs, but who gets to wear them? It seems only a very narrow body type is celebrated for wearing these styles, and it’s still dictated by the male gaze. Social constructs like Theiss’ Titillation Theory focus on what men find desirable, and it’s usually men who dictate the policies that punish a woman’s nakedness on social media, especially if she exists in a larger body.

In an effort to subvert that gaze, a growing chorus is calling out Instagram for favouring thin, partially-clad women while censoring larger bodies, while other local creatives are using revealing clothing as a form of resistance. Sydney-based designer Niamh Galea, founder of the size-inclusive label Ramp Tramp Tramp Stamp, tells me she’s been reflecting on her body’s place in the world ever since she was a young girl, adding this can be a common experience for women, queer people and people of colour.

For so many of us, particularly those who went through puberty early, our clothing choices were initially rooted in rejecting desirability.

“I’ve tried fighting against my body, covering it up, but have come to a place of accepting that no matter how I try to hide it, I’ll always be subjected to the opinions of others,” she says. “With this in mind, I personally find owning my own objectification – and using clothes as a way of reclaiming my visual identity – to be both powerful and healing.”

Recently, actor and model Milo Hartill was accosted by a stranger for not covering up their body while riding on a Melbourne tram. Milo, who (like me) self-identifies as fat, was wearing a crop top and pants, leaving a small panel of flesh uncovered, which the stranger poked with their walking stick, remarking that her clothes were “too small” for her.

She joked, “It wasn’t even like I was wearing clothes that were revealing, you know, I often wear a bikini and heels and call it a day. I was like ‘Diva, if this is offensive to you, wait ’til you see what I wear most of the time.’”

Radical reveal

For people who don’t conform to the ideals defined by the male gaze, the act of wearing anything, let alone something ‘revealing’, is political. Like the reactions Milo gets about their outfits on the tram, Niamh says her label receives a similar response. “Sometimes I’m shocked at how radical my clothing is interpreted as.”

I wonder if the response to Censori’s dress might have been different if her body was less voluptuous. It seems to me that a culture that celebrates Coperni spraying a dress onto a naked Bella Hadid is one that would embrace The Invisible Dress. Where is the line between classless and chic? If Janet Jackson had been a white woman, would she have been able to bounce back?

Society is uncomfortable with a woman’s nakedness, but even more so with nakedness from people who don’t fit supermodel beauty standards when it comes to body size and shape.

In this way, wearing revealing clothing can be a radical act of resistance, a sentiment Niamh agrees with. “By openly and shamelessly being yourself, and embracing your body by showing it off, you’re allowing people to slowly but surely embrace themselves. I hope that when people see me strutting down South Dowling with my muffin top out and in an asymmetrical sheer top that makes my boobs look lopsided, they might think ‘I can accept myself too’.”

This article was originally published in Fashion Journal issue 197.

For more on size inclusivity, try this.