How to be a creative thinker: An excerpt from Roya A Azadi’s new book

PHOTOGRAPHY BY TOBIAS ROWLES

WORDS BY ROYA A AZADI

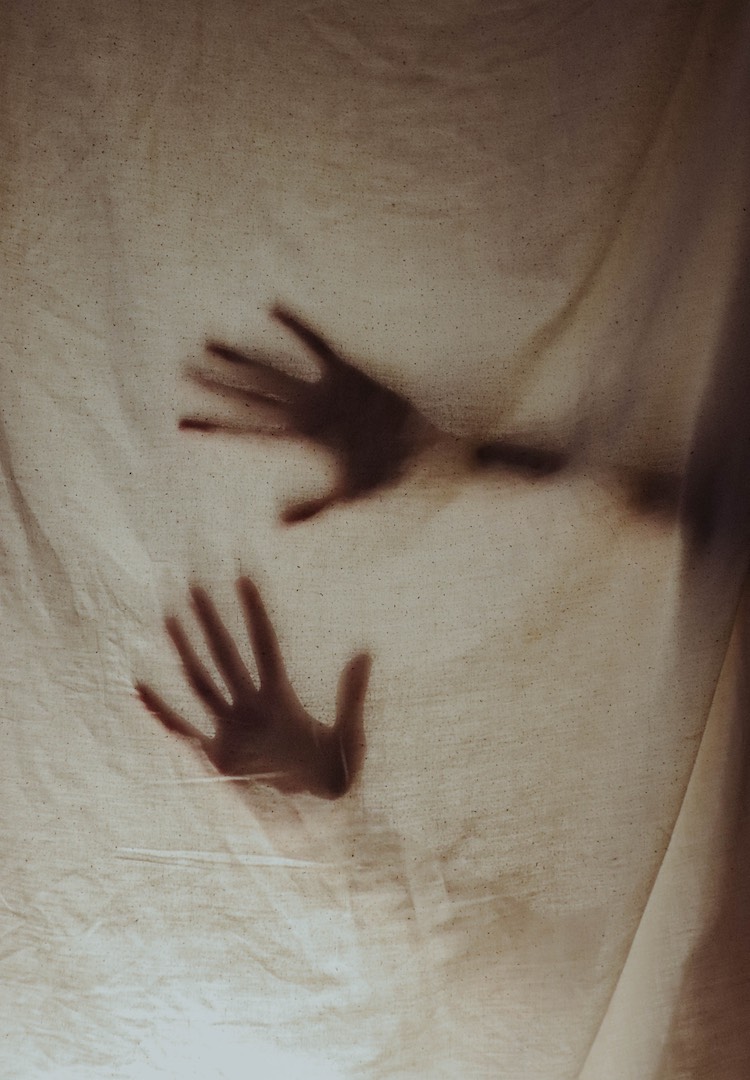

An exclusive excerpt on the importance of daydreaming from How to be a Creative Thinker.

I love driving. The longer, the better. When I can hear the hum of the car and the steady beat of the music with a long stretch of road ahead of me, my mind will settle into some kind of rhythmic zen.

I have just enough tasks at hand to occupy my mind, between the spatial Tetris of traffic and the sounds of the music, but they’re familiar enough I barely need to think – I’m on autopilot.

We like nosy people. Don’t be shy, head to our Life section for more.

And the longer I’m able to sit with the boredom, the more likely I am to start hearing them talking; that is, my consciousness. That meandering stream of inner chit-chat that is constantly expressing itself, though I can rarely hear it for the noise of podcasts, phone calls and notifications.

Long drives are my shortcut to daydreaming. That strange lucid state of non-thinking allows fragments of thoughts, memories and feelings to collide and dance up to the surface. It’s what happens after I’ve allowed myself to become bored.

The wandering state of mind Arthur Fry was in when he came up with the idea for the Post-it while singing in his church choir, or Andrew Stanton was when he got the idea for Wall-E’s face while at a baseball game using some binoculars. Richard Feynman developed his theories of quantum electrodynamics while watching a student spin a plate on his fingers, ironically, after he had decided not to focus on physics anymore.

It’s what comes after, if you can tolerate the boredom. A mode of deep relaxation and idleness that doesn’t start the flow of your consciousness, but rather lets you observe what is often happening just beyond your metaphorical earshot.

Can you remember the feeling of walking down a street on your own and a great idea suddenly coming to you? In that moment, you were daydreaming, your mind playing hopscotch with all the dots of ideas bouncing around in there, seeing which ones bounced off each other in the right way.

The key aspect here is the hearing. What use is your mind connecting all these dots if you’re too distracted listening to a podcast or checking your phone to hear the results? Daydreaming is a passive act – all you need to do is put away the distractions, and listen.

Idle hands are the devil’s work

Daydreaming is involuntary. Even if we don’t often have experiences where the chit-chat of our daydream becomes as audible as a voice in our ears, we all mind-wander so frequently that a study by Harvard psychologists Daniel Gilbert and Matthew A. Killingsworth put it at approximately 47 per cent of our waking hours.

Why, for something as natural as sex, sleep and going to the toilet, is daydreaming treated with so much shame? Why do we judge with titles like ‘space cadet’ or ‘unfocused’? Freud even took it further, with his damning description of daydreams as an ‘infantile’ attempt at escaping the duties of reality and living in a world of fantasy ‘wish fulfilment’ instead.

The world we live in is driven by efficiency and productivity. One day we’ll say it’s a neoliberalist hangover, but right now we’re still in the throes of a night of heavy drinking.

Daydreaming doesn’t fit into a paradigm where our value as a human is measured by what we produce for the free market. A 2012 study of 5000 workers across the world found 80 per cent of them felt the pressure to be productive, not creative, at work.

Some workplaces – particularly advertising agencies and tech start-ups – have gained notoriety for having ping-pong tables and candy walls to encourage wandering of both the physical and the mental kind, but the average office team is propped up by an invisible treadmill of productivity.

The wandering mind

The Default Mode Network (DMN) – a decidedly unromantic name for a place where something so innately you occurs – is the part of the brain that fires up when we are experiencing our intuition. It’s the place where our sense of self and identity washes around as it formulates and reformulates with each life experience.

Neuro-imaging of people engaged in an ‘idle mind’ (aka, not doing much of anything) show our brains don’t even come close to resting when not engaged in executive functions of self-control, decision-making and goal-oriented focus.

The brain stays very much alive and doing something nobody expected: not only was the DMN lit up, shuttling thoughts of self, intuition and random mind-wanderings around, but so was the prefrontal cortex – the area most associated with the executive function.

In fact, the stronger the relationship between the DMN and the prefrontal cortex, the more novel and useful someone’s response to a challenge. In other words, the more someone daydreamed, the better they were at real-world problem-solving.

Studies have shown that children who daydream are better at self-directed focus and executive function which is obviously and probably an indicator of a more resilient and thriving adult. Research has also shown that those who allow themselves to daydream have more efficient brain systems overall. To sum it up, more daydreaming, more DMN activity. More DMN activity, more creativity and better overall brain function.

While neuro-imaging can only show correlation, it’s a comfort to know that centring our sense of self and allowing our intuition to flourish is intrinsically tied to our creative ability and predication to problem-solve. It’s strange to know that modern science has worked out where something as abstract as ‘self’ occurs in the brain, but heartening to know that daydreaming perhaps could be the cure to getting back in touch with your intuition.

Practice with no limits

Sit with your creative mind rather than with the limitations of your skills or money. Learn to listen to the daydreaming and in doing so, generate a list of ideas that can become a foundation for future concepts.

• Write 100 ideas of what you would do if you had all the time in the world, all the help and all the money. No limits of any kind.

• After you begin writing, don’t look up. Not even to see if you have written that idea before.

• You must do this in one sitting.

Keep this list, and refer to it when ideas are needed.

This is an edited extract from How to be a Creative Thinker by Roya A Azadi, published by Hardie Grant Books, RRP $19.99, available in-stores nationally.