The attraction of external distraction

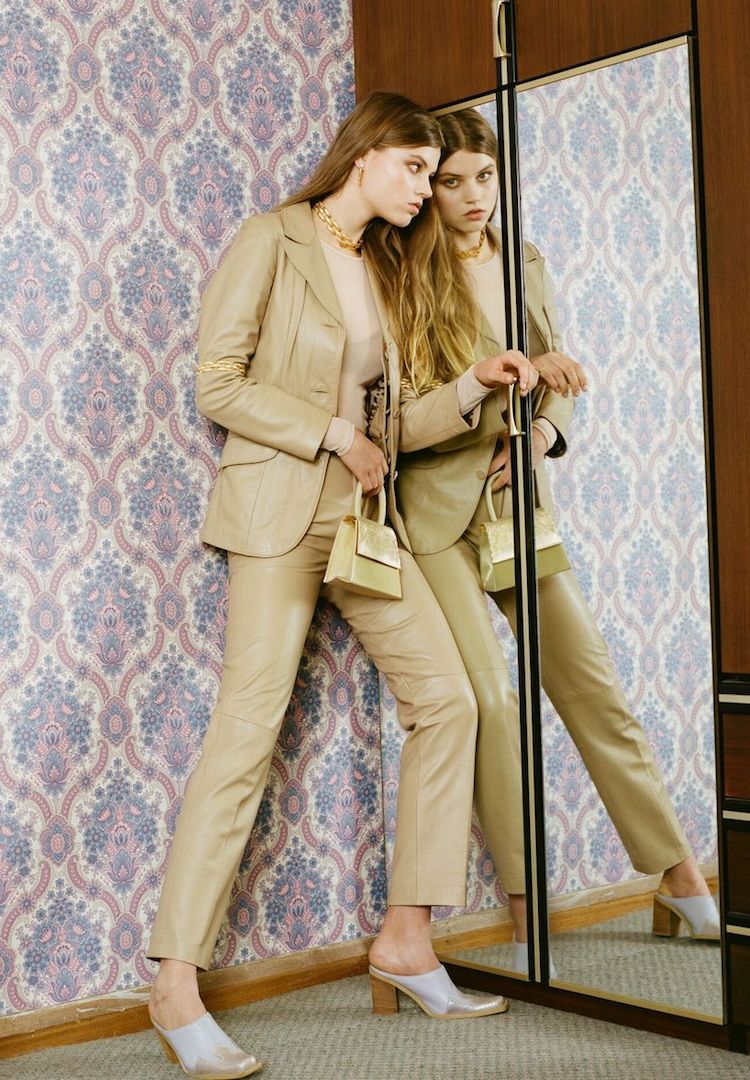

PHOTOGRAPHY BY JORDAN DRYSDALE

WORDS BY AMY ROSE DORRINGTON

Reflections on busyness as escapism in a time of isolation.

As a result of COVID-19 chaos, I have been in isolation and without a job for almost a month now. I’m hyper-aware that I am one of the lucky ones. All this spare time I suddenly have is a luxury. I might not be spending it the way I would ideally like to spend it, but I’m realising that perhaps this forced downtime is creating space for me to separate my true feelings from the attraction of external distraction.

In my normal life (what even is ‘normal’ anymore?), my typical behaviour was to entertain myself by filling up every hour of every day with stuff. Making new Spotify playlists on my walk to work. Swapping weekend stories with friends at lunch. Taking the edge off a stressful day by doing an intense pilates class or going for mid-week wines. Cooking dinner for my housemate. Bingeing the latest Netflix obsession while blindly swiping through Tinder. Mindlessly scrolling Instagram. Delving deep into my latest book purchase to divert my mind from the racing thoughts and anxieties that seem to be most active late at night. Finally getting to sleep only to repeat it all the next day.

Without question, this constant state of busyness isn’t unique to me. It’s a byproduct of a world where being busy is regarded as a badge of honour, proof of productivity, evidence of self-worth. Existing in a digital age where 24/7 access to information and communication means it’s easy to be distracted all. the. time. If I know I have a rare weekend free of commitments, I find it near-impossible to just do nothing. I make plans to avoid the daunting possibility of spending a Saturday night at home alone, yet complain that I’m exhausted or that I never have enough spare time.

But I know – at least to a degree – that this behavioural pattern is also my coping mechanism. For as long as I can remember, keeping busy has always been my strategy for getting over something difficult. A bad breakup, a toxic friendship, housemate dramas, a crappy week at work.

When I was 23, my way of dealing with the sudden and devastating death of my first serious boyfriend was to distract myself. The day after his death, I went to work. I didn’t know what else to do. In hindsight, I guess I was in a state of shock, but I knew that if I stayed at home, I’d feel helpless and consumed by my thoughts, and there was no way I was going to allow myself time for that. Going to work was my way of controlling – or escaping – the situation with external distractions.

Last year, when we found out Mum’s cancer was spreading more rapidly than anyone had anticipated, we rushed to her hospice bedside to fill her final days with as much joy as possible. My uncle played her favourite songs on his acoustic guitar until his fingers were raw, and we sang together, day and night, by her bedside, for two days straight. It was a comfort and a distraction – for Mum, and for us – from the overwhelming reality of the unchartered territory that all of us were facing.

Even in the week or so after her death, we didn’t stop. We filled our days planning her memorial. Driving to her favourite place down the coast to scatter her ashes. Thanking people for the endless flowers and messages of sympathy. Suddenly it was Monday and I was back at work, less than two weeks after her death. My brother had flown back to Sweden. Dad had gone back to work. The extended family had returned to their homes. I missed my work friends. I didn’t want to be at home alone with my thoughts.

When I returned to work, some people asked how my ‘break’ was. How I enjoyed my ‘holiday’. They meant well. But I was exhausted. I hadn’t had any time to even acknowledge, let alone process my emotions. I hadn’t allowed myself the opportunity to be still. I didn’t want to. I realised nothing scared me more than being forced to confront my thoughts, without distraction.

What if this time in isolation is teaching us how to be okay with our own company? What if this time – away from our friends, lovers, work offices, favourite bars – is exactly what we need to face the uncomfortable and the unfamiliar? To allow room for those suppressed emotions we’ve had safely locked up, buried in the back of our minds for so long?

Maybe this constant state of busyness is serving as a buffer to give us the time we need to continue with the day-to-day before we’re ready to admit the existence of our most challenging thoughts and emotions. I have no doubt a degree of distraction serves a purpose, at least for me.

With that said, if like me, you’re in the privileged position where the worst of your worries is being at home in isolation, perhaps this is our chance to stop ourselves from being seduced by the attraction of external distraction. To embrace the stillness. To find comfort in discomfort. To feel what is real.

For me, that’s scary as fuck, but it’s also a defiantly liberating act of self-love.