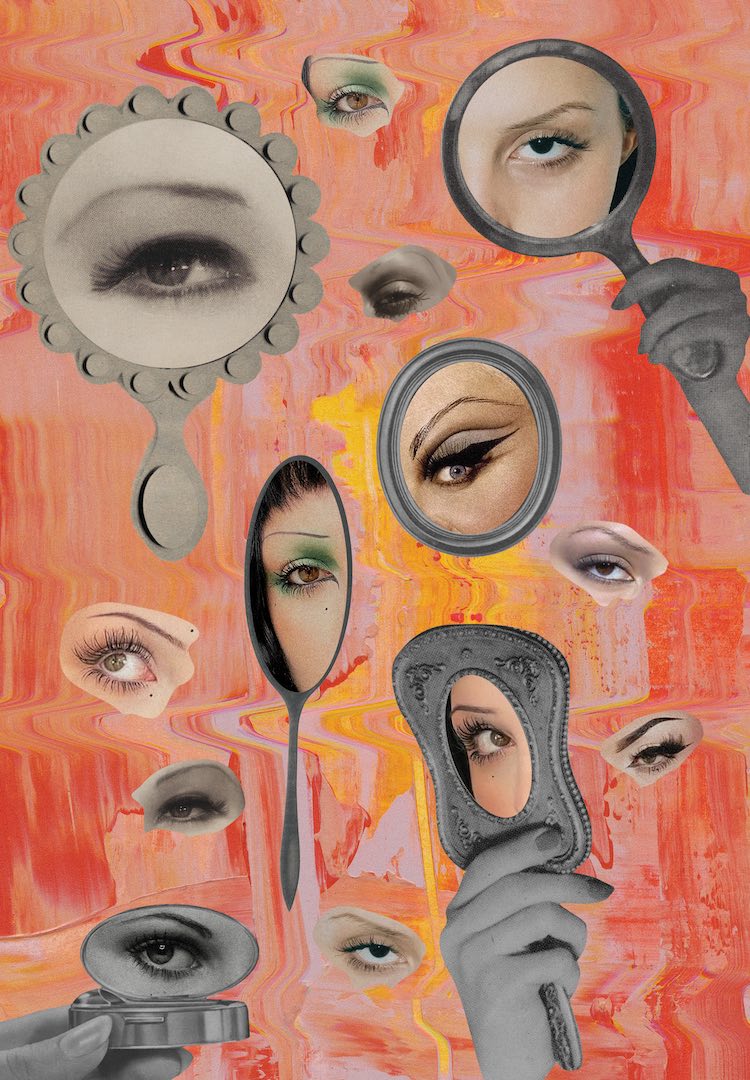

Why do we still struggle to present women in film as unsexy?

WORDS BY Ella McEwan

“Something as simple as a walk to Coles would have me bent over backwards trying to get the perfect look. Did I look good buying grapes?”

Over the last few years, I’ve been so excited by the calibre of female-driven films like Booksmart and Shiva Baby. Call me delusional but based on the representation of women in these films, I thought we were over needing women to constantly look sexy despite the story being told.

Maybe it was just a shift in what I was consuming, but when I took myself to see Where the Crawdads Sing, I thought I was going to get the rough and tumble marsh girl from the book. What I got was nearly exactly the opposite.

For more content like this, tap through to our Life section.

If you’ve not seen the film or read the book, our heroine Kya is painted as an ostracised loner with only enough funds to eat, rejected by the strict 1950s town she lives in and all but abandoned by her family.

Given this description, imagine my surprise when I saw curtain bangs only a Dyson Airwrap could give (how does anyone without social media have Matilda Djerf hair?) and beautiful dresses that were more likely to be in your local vintage shop than the wardrobe of a self-proclaimed marsh girl.

It could be a silly thing to fixate on, but it was all I could think about – the ridiculousness of not allowing someone to look a little grubby as they trot around wetlands, simply because they’re a woman.

Personally, media has always affected how I see myself. I used to watch a movie or series and then plan out how to morph myself into the main character, murdering my hair with a straightener or making mum buy me the right school shoes (you know the ones) à la Puberty Blues.

While those are little things, they inevitably got bigger, and I can now see how damaging not being able to live up to the same standard as the women I saw on screen was.

Something as simple as a walk to Coles would have me bent over backwards trying to get the perfect look. Did I look good buying grapes? Will my hot local barista still be in love with me if I turn up in sloppy sweatpants without a stitch of makeup? Or more seriously, what will happen if I’m not the skinniest or prettiest version of myself I can be?

I admit I wasn’t in the room when the hair, makeup and costuming decisions were made for this film, but with no context given for those choices, it got me thinking about how my internal battle with self-confidence and not allowing women to be ‘unsexy’ go hand in hand.

To unpack this more, I reached out to Professor Lisa French, RMIT’s Dean of the School of Media and Communication. Internationally recognised for her work on gender in film, Lisa tells me how lack of visibility not only affects that person, but society as a whole. “If you don’t see yourself, you can’t imagine yourself. If you never see yourself, you feel like you don’t exist, you feel like you’re alone,” she says.

While it’s easy to label this an issue exclusive to Hollywood, everybody suffers from stereotyped representation in media. Men are forced into these boxes just as much as women, usually into the role of provider or macho hero in much the same way as women are often the inexplicably sexy caregivers or femme fatales.

“It’s the same in relation to race, if we don’t see different gender identities and racial and sexual identities or cultural identifications then we are less socially cohesive. We don’t know anything about them, and those people are then isolated,” Lisa continues.

Even with a (perhaps performative) push for diversity, in 2021 just 41 of the year’s top 100 films had a female lead or co-lead, and of those, just under 60 per cent of speaking roles were given to White actresses.

From the outside it can seem like we’re moving in the right direction, with Oscar wins for directors Jane Campion and Chloe Zhao in 2022 and 2021 respectively.

Despite the success of these films, Variety reported that only 17 per cent of the top 250 highest-grossing movies of 2021 were directed by women, down from 18 per cent the previous year.

“I would think that most cinema is created by male gatekeepers. Women make up more than 50 per cent of the population, so we aren’t using all our creative talent or getting those perspectives, so of course, our view is a masculine one. If we have enough women making films, then we’ll get female perspectives, and get films that feel real and authentic.”

As for media bucking the trend, Lisa points to television. “It depends what the media is – feature films just tend to be one they’re not getting into, but in other areas, there’s more of a box office for that now. In television, women are making greater gains and there’s a lot of appetite for women’s stories,” she says.

The Maid and The Mare of Easttown are two shows Lisa recommends for anyone looking for something a bit more authentic. Both series are able to tell their female protagonist’s stories without glamming them up excessively. It might be too late for 1950’s marsh girls to get their representation, but for her contemporary counterpart, the issue is still one we’re still tackling.

“It’s taking a really long time to level the playing field. The implication of that is there’s a lot of really great stories that we will never see, ones that as a woman I might identify with,” notes Lisa.

“I do think that women don’t objectify, sexualise and degrade women on screen [in the same way men do]. There are always exceptions, but if we have more female filmmakers, we’re going to have a greater mix.”

By getting diverse voices into the filmmaking, the hope is that we can see more of ourselves and others and ditch the old outdated rules about who we should be and what we should look like.

To get a little mushy, I just want to see women on screen that reflect the diversity that exists around us. Ones that look like me, my friends and family, you and yours, or women you went to high school or university with.

And don’t get me wrong, some women do look as glam as movie stars in real life. There’s absolutely nothing wrong with looking done up or down, but maybe it’s time for Hollywood to let marsh girls be marsh girls, and show us greater diversity in the way women present themselves.

If you’re struggling with body image issues, you can call the Butterfly National Helpline at 1800 33 4673 for free and confidential support, or email or chat to them online here.