Blockchain is being introduced to fashion supply chains, and it might hold the key to transparency for brands

WORDS BY ISABELLE SACKS

Could this be the future of ethical consumption?

If you’re anything like me, you started hearing about blockchain a few years ago in the context of cryptocurrencies like bitcoin but felt your eyes glaze over when someone tried to explain it to you. I know I’ve heard a ton of ‘simple’ definitions like this: “blockchain is a distributed, decentralised, public ledger”, which means absolutely nothing to me.

So when I heard that fashion brands were starting to use blockchain to create more transparent, ethical and sustainable supply chains, I knew that it was finally time to get my head around this technology and its application.

From what I can gather, blockchain is essentially a highly secure form of record-keeping where ‘blocks’ are verified pieces of transactional data, stored in a ‘chain.’ In the fashion industry, it can be used to help create more efficient and less opaque supply chains.

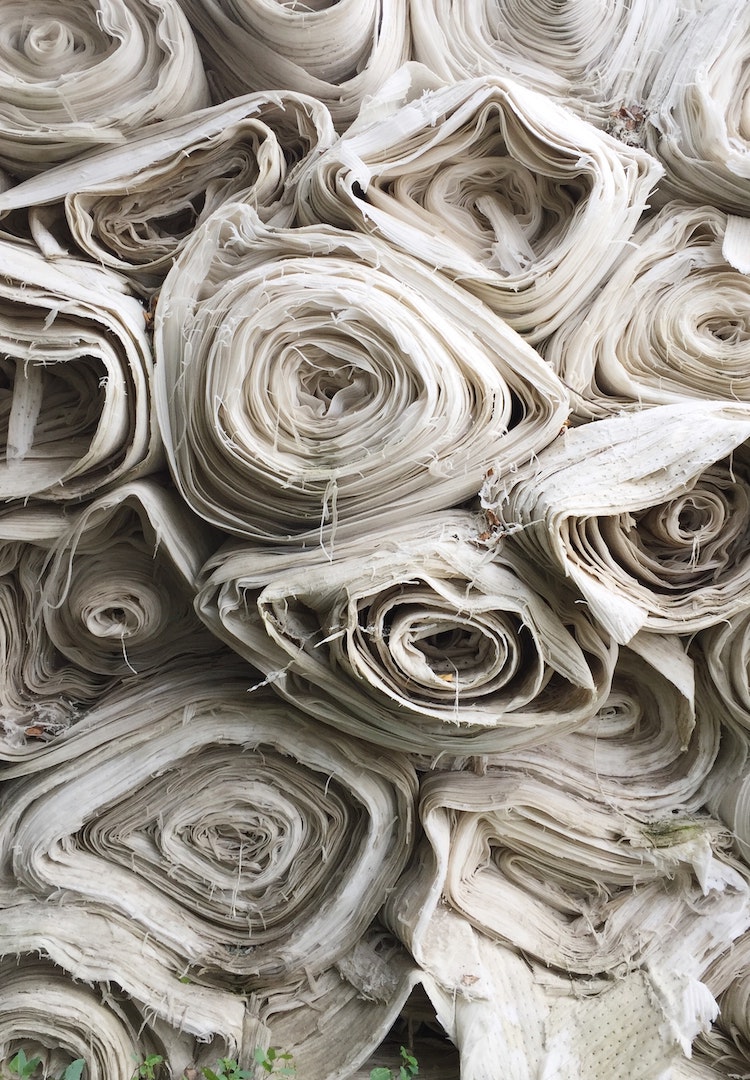

I spoke to Mary Hall, Director of Blockchain at American tech giant Oracle, about what makes it so valuable in the area of supply chain management, and she says that it comes down to transparency. “Designers, the brands, the suppliers, and finally the customers and trading partners, can actually see information about the products they buy – from the sourcing, the materials used, the dyes used, the fabrics, all the way down to the final product when it’s hitting the store shelves.”

In practice, Mary explains, every single component of every product worldwide can be assigned a unique code at the start of its production. This code is time-stamped, secure, and trackable in real-time so that consumers and retailers alike can rest assured that they have all the information about where their garment is coming from.

“Today’s consumers want to make conscious buying decisions,” says Mary. “They want to vote with their money… they want to know the whole picture about the journey the product has gone through before it reaches them.” Through this level of radical transparency, blockchain can help empower consumers to make buying decisions that align with their values.

Ethical labour and sustainability

One key aspect of blockchain is its decentralised nature. “There’s no one administrator,” Mary explains. ”The data is shared by multiple parties, and if someone tries to tamper with the records, the tampering is apparent to everyone on the chain.” This feature can have a lot of applications, but ensuring that all actors participating in the supply chain are adhering to sustainable and ethical labour practices may be chief among them.

Time and time again, we see companies shocked at the conditions under which their goods are produced when the media highlights it. Just last year, a Four Corners report found that six retailers operating in Australia – Target, Cotton On, Jeanswest, Dangerfield, Ikea and H&M – were sourcing cotton from the Xinjiang province in China that may have been produced by Uighurs, a Turkic-speaking minority ethnic group who were forced into factory labour.

This prompted many of the companies to undergo investigations, but it raised a bigger question: why don’t these companies know where their materials are coming from in the first place? Using blockchain for supply chain management could provide everyone involved in the life cycle of a product with transparency about the way it was produced, right down to the individual alpaca who so graciously provided the wool for your cashmere jumper.

In this way, blockchain becomes not only a traceability tool but also a driver toward sustainability. Transparency on its own doesn’t mean much – once companies have their supply chains tracked and wide open to the public, implementing fairer working conditions and environmental policies should be a natural step.

Transparency is about building a good reputation after all. “Sustainable practices are now big marketing for the fashion industries,” Mary says. With blockchain, consumers can look beyond the greenwashing and choose companies that are putting in the work when it comes to environmentally friendly practices.

Authenticity

Counterfeit fashion is big business and is only getting bigger, with the OECD estimating that it represented 3.3 per cent of global trade in 2019, roughly $700 billion per year. A big part of the problem is that there is no simple way to track the provenance and authenticity of goods using even the most sophisticated centralised systems, as they are highly susceptible to cyberattacks and insider fraud.

Blockchain can be used to create a unique digital identity for an item, assuring the authenticity of both new and vintage goods while also recording information such as transfers of ownership and conflict-free designations (i.e. confirming that pieces are not blood diamonds or are produced without slave labour).

Vintage fashion and secondhand luxury goods have become a booming business in the last few years – think platforms like Vestiaire Collective and TheRealReal – and blockchain could prove extremely useful when it comes to assuring consumers of the authenticity and quality of the items they’re splashing out on. “With that transition, people are going to want to verify the products,” Mary says. “People want to know before they invest in that piece, that it is the real thing.”

Is it worth it for companies though?

That’s sort of up to us, the consumers. Blockchain supply chain management can be a big investment to implement, and radical transparency may not look at all attractive to companies whose business models rely on keeping costs low for consumers by cutting corners during production. Right now, if we want fashion that is sustainably and ethically produced, we have to be willing to pay a premium for it.

Mary says that 77 per cent of organisations believe that using blockchain for supply chain management is a competitive advantage, and those organisations may be right in the long term. One in four young Australians says that they are concerned about the environmental impact of the clothing they buy, and one in five are worried about ethical issues such as sweatshop labour, according to a survey by Amplify. If we want the companies we buy from to reflect our values, we must demand it by voting with our dollars.