Inside the studio and design philosophy of made-to-order Melbourne label, Kalaurie

Images by Anu Kumar

Words by Holly Bodeker-Smith

Sanctuary.

Most people discover their passions later in life, while a few get to know them from an early age. Kalaurie Karl-Crooks, an Australian fashion designer, falls into the second group. When Kalaurie was growing up, her parents would take she and her three siblings on weekend grocery runs. After stocking up on food, they would hit the op shops. It was there, exploring the racks of used clothing, that Kalaurie’s passion for igniting new life into used objects was born.

“If I wanted a new pair of jeans, my parents would give me five bucks to spend at the op shop,” she says. “But they never winced about spending money on creating art or books to read. If I wanted to sew or paint they would take me to the art shop and get new materials right away.”

Kalaurie’s parents rarely bought anything new and loved antique furniture. When she wanted a mobile phone for her 16th birthday, they bought her a sewing machine instead. And when she was four-years-old, they bought a second-hand yacht for their family of six to live on. They spent two and a half years travelling on it, sailing through the Americas before moving to Australia in 1998.

“We didn’t have rubbish disposal, so we bought everything in bulk and kept our plastic rubbish until we got to a port,” she says. “We couldn’t hold onto much… I lived in a bunk in the living room and everything I owned had to fit into an A3 cupboard. That was a very minimalist time in my life, but I wouldn’t describe myself as a minimalist now.”

It wasn’t until they returned to dry land that Kalaurie became truly aware of – and disturbed by – waste. Her parents bought a hospitality business, where she helped out as a dishwasher. “I was shocked at how much food I had to throw away – to see that someone had ordered bacon and eggs and eaten everything but the bacon,” she says. “At home we finished everything our parents cooked, or we would eat the food from the cafe that was about to expire.”

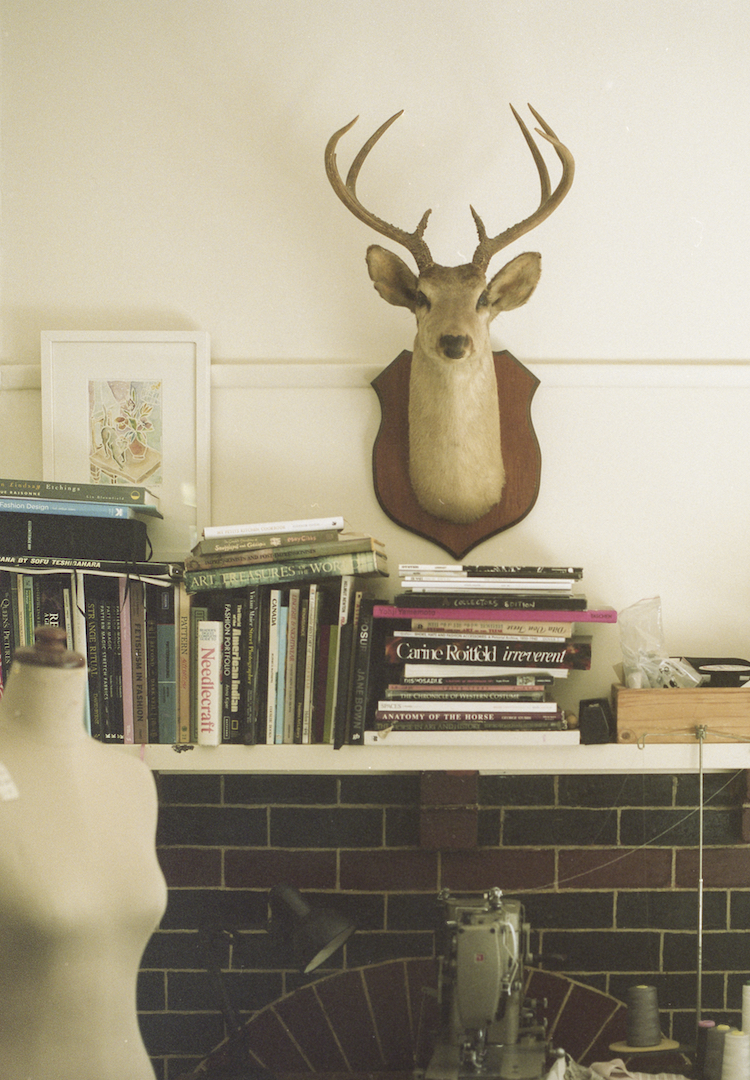

Though Kalaurie had already taught herself how to sew, she didn’t immediately commit to her love for fashion design. After finishing school she moved to Melbourne and briefly studied costume design before applying for both the Fine Arts and Fashion programs at RMIT. When she got into both, she chose Fashion on a whim. “I’m a very hands-on person and I was always going to do something creative-driven,” she says.

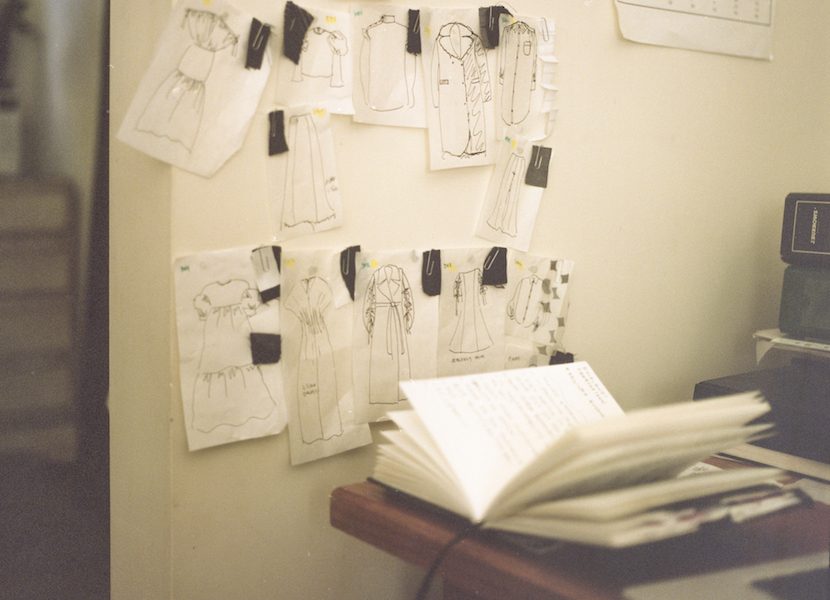

At fashion school, Kalaurie quickly noticed the magnitude of waste in the design process. “Students would throw away so much paper, cardboard and fabric. So I would go into the recycling bin, pull out scrap paper and use it for patterns,” she says. This idea of eliminating waste became the platform for her education, and culminated in her designing her graduate collection using mostly deadstock fabric.

Today, her aversion to waste is stitched into every garment she makes for her eponymous label, Kalaurie. She designs made-to-order luxury womenswear from her studio in Melbourne. She buys unused organza, cotton, linen, viscose and suiting fabric from fashion houses or wholesalers that sell surplus fabric. These are then repurposed into timeless garments for women.

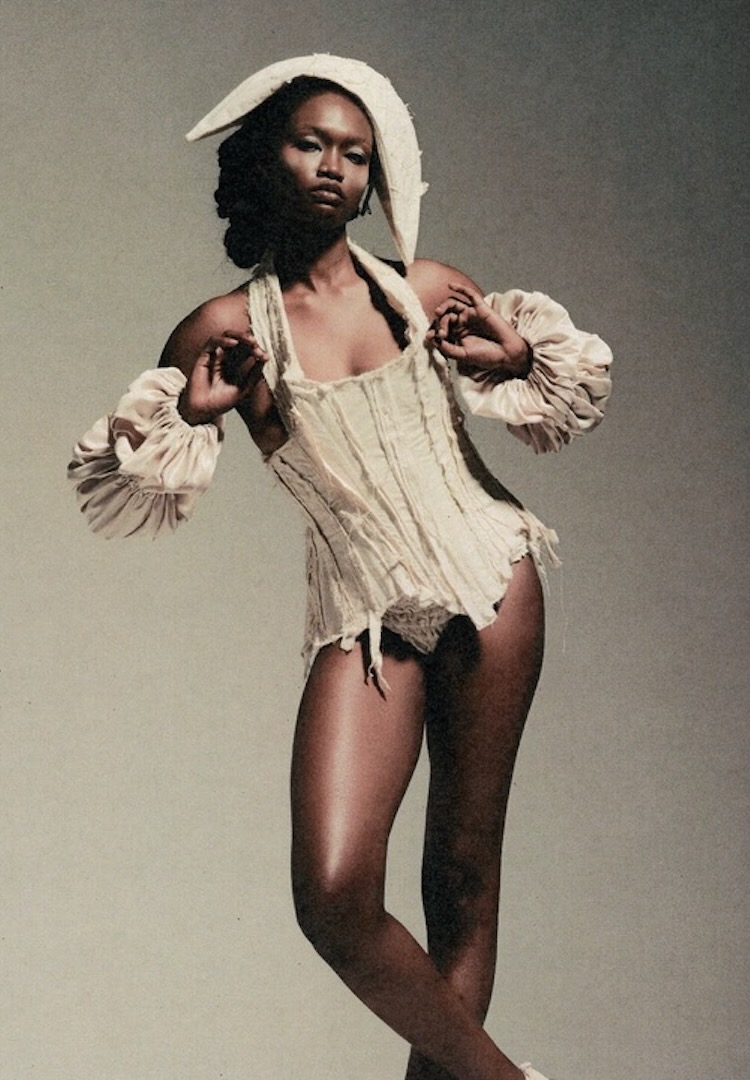

Many of Kalaurie’s designs take inspiration from Victorian-era clothing. Black dresses are relaxed or ruched around the shoulders and bust, leading into a cinched waist and then a billowing skirt. She also makes statement shirts with eccentric details; her latest range includes one with panels of pleating hanging from the collar.

But using deadstock materials comes with its limitations. It’s difficult to source, and once it runs out there’s no ordering another roll. For Kalaurie, it comes with the territory – and it’s a territory to which she’s willing to adapt. “I like knowing that I can only make eight dresses from a certain fabric. If it runs out, it runs out and we move on.”

Her made-to-order manufacturing model also leaves significant room for experimentation. “It’s easy for me to make custom pieces using fabrics from my archive,” she says. For example, if a customer wants a shirt in a different colour, she will show them the fabric she has on hand and they work from there. “It’s special working with clients one on one to make a one-off piece.”

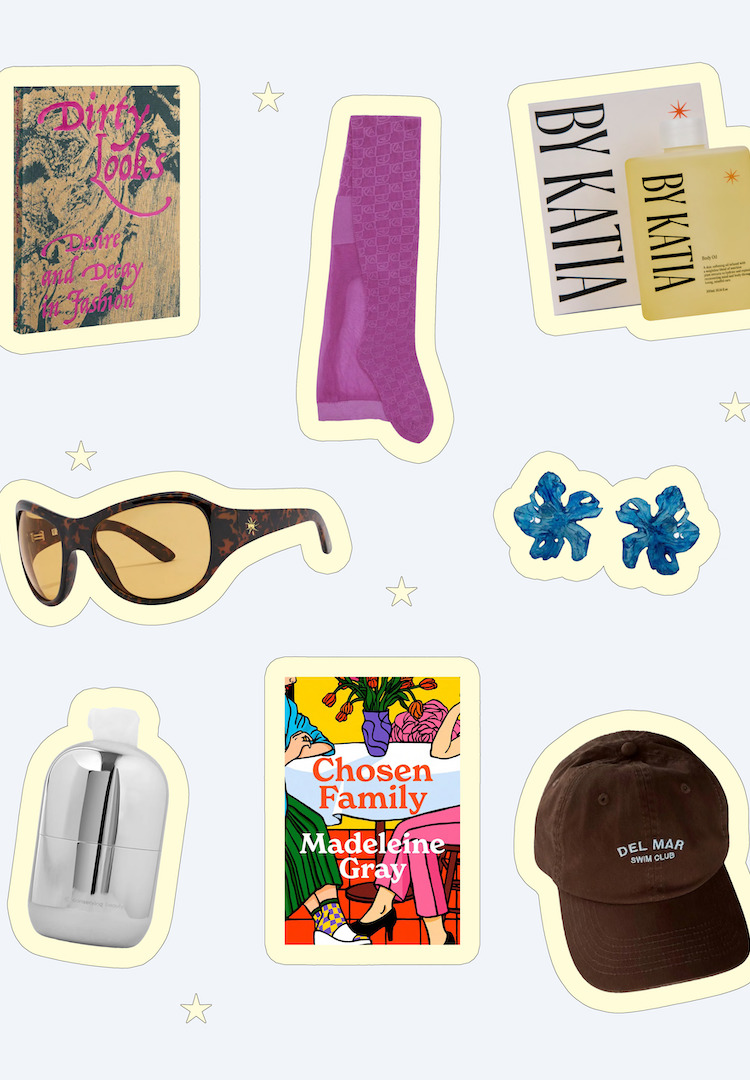

By inviting her customers into the fold and only making to order, Kalaurie slows the production process right down. “None of my pieces are immediately available. [Customers] wait three weeks for a garment to be made, and they are happy to. It creates more emotion and is so rewarding for them,” she says. In doing this, she also restores a sense of anticipation for her customers. It is a far cry from the quick, transactional nature of buying fast fashion.

Kalaurie also has the full power to determine how much waste her label produces. “It’s fashion, there is always going to be some waste,” she admits. “But I try to use as much as possible. I give fabric scraps to crafty people I know, and I make quilts from shirting fabric scraps. I pull buttons and zippers off old toiles to reuse, and if a designer is clearing out their studio I’ll buy their rolls of cardboard for my patterns.”

Kalaurie’s most remarkable trait might be her continuous refusal to lean into the single-use, throwaway culture of modern society. Her most-prized possessions are the hand-me-downs from her grandmother that she uses constantly. There are the china plates that she and her partner eat from every day. When they break, she holds onto the fragments. One is perched her kitchen window.

And there is a fur-trimmed, orange coat from the ’70s. “I’m sure my grandma saved it for special occasions, but I wear it every day in winter.”

Minimalism is just one form of backlash against the excesses of industries fuelled by capitalism and shamed by environmentalists. But it brings its own set of challenges when the masses adopt it. Indeed, the Marie Kondo effect saw op shops the world over become overrun with unwanted donations. Even in trying to achieve minimalism, we continue to throw so much away.

Kalaurie should be Kondo’s teacher. She uses it up, wears it out and makes it do. For her, the key is to imbue any used object with new meaning before passing it on – whether it’s a broken plate, a square of discarded cotton, or a roll of unloved fabric that she turns into a luxury garment.

“My customer collects beautiful things that make her feel good. She knows she is buying and waiting for a thoughtful, one-of-a-kind piece – something she will wear for a lifetime and pass onto her family down the line.”