Shrinvanti Roy’s graduate collection explores rhythm and repetition through textiles

The rhythm of the textile.

Once again, Fashion Journal is the supporting partner of Virgin Australia Melbourne Fashion Festival’s National Graduate Showcase.

The 12 finalists for 2020 have been announced, and they’ve given us an insight into the process behind the collections they’ll be showing.

Next up: Shrinvanti Roy and her graduate collection Use of Textiles in Art Therapy.

Please introduce yourself to our readers.

Born in India and based in Melbourne, I was educated at the National Institute of Fashion Technology Bombay. After completing my undergraduate degree, I worked with Converse and other brands for three years as a womenswear designer, where I gained industry experience before embarking on my Master of Fashion (Design) at RMIT.

Tell us about your collection.

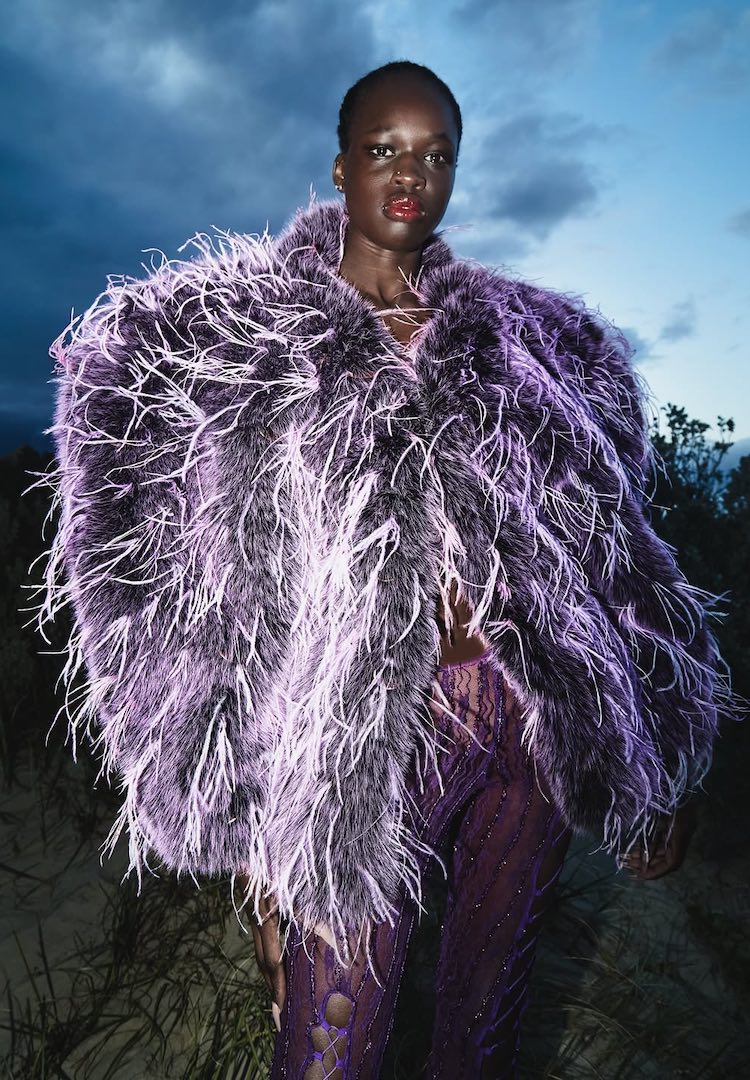

My research-driven project is based on the principles of art therapy. Use of Textiles in Art Therapy explores rhythm and repetition, and how these concepts can manifest in textiles and garment making. The individual textile art pieces are formed through a process that generates rhythmic responses in our body. Focusing strongly on textiles and textile making techniques, the project highlights the importance of rhythm and repetition in therapy, exhibiting the concept of ‘flow’ in a garment. It is an attempt to analyse and explore research stating that optimal creative experiences are more likely to occur when a task is repeated a certain number of times with extreme focus and attention, to a point that this becomes a rhythmic, reflective response. This very state of flow is therapeutic.

When did you know you wanted to get into fashion design?

Ever since childhood, I was always more inclined towards art and textiles than the generic scientific studies I was enrolled in as a high school student. It was at that time, when my chemistry book was filled with sketches of random objects I saw and observed, and my answer sheet was filled with horrendous scores, that I finally made peace with the fact that art was something I wanted to pursue as a career. Not knowing which direction to take, I trusted destiny to shape my life. Months later, I cleared the entrance examination of the top fashion and design college in my country with a global ranking of 91. In a country with the second largest population in the world, my scores helped me make better decisions about my life. I chose fashion as a major and enrolled in to the National Institute of Fashion Technology in 2011.

How would you describe your design style?

My design style has always been nature-inspired, and even my previous projects have been heavily influenced by earthy themes and colours. I believe that everything started with nature and will eventually merge back into it. I have always heavily quoted the biblical reference “Dust thou art, to dust returnest” for every major decision, relating to both my design aesthetics and life in general. My designs are raw and exposed, just like the bark of a tree or a newborn sapling. The colour palette reflects the gradual colour changes in nature throughout the process of birth, death and rebirth.

What were the major points of inspiration for your graduate collection?

Back in the first semester when I was interning for Arts Project Australia, the concept of therapy and healing was heavily ingrained in my mind. After working with some intellectually disabled artists in a beautiful studio setup and getting to know their life and beliefs through close personal interaction, I concluded that art therapy is a very strong procedure to heal people with traumas and anxieties. I witnessed the artists using different mediums to express their desires and emotions. Paint, dance, photography and music were some of the prominent ways, which made me wonder about using textiles in therapy and expression. Some of my main inspiration points were also triggered by my brief visit to the Royal Botanical Gardens, where I spent a whole afternoon observing different elements of design in nature.

How do rhythm and flow translate into a physical garment?

Rhythm and repetition are the major aspects of this research project. Rhythm could be a virtual belief or entity. Rhythm could also be the outcome of a repetitive procedure which can only be experienced, not seen. Flow is often a state of being. The challenge was to create something that would reflect a virtual emotion into a real, tangible object. The physical garment could be the outcome of a rhythmic response generated by a repetitive procedure, in which case the garment becomes a manifestation of thoughts and experiences. On the other hand, one could also focus on the different characteristic properties of rhythm, repetition and flow, mostly metaphoric in nature. After having a clear idea about these properties and hidden meanings, one can easily demonstrate the same ideas by relating them back to properties of specific textiles, yarns, garment silhouettes or shapes.

Tell us about the experience of putting together your graduate collection.

Honestly, for the longest period, my project was mostly research and papers. I had a tough time putting all my research into the idea of a garment collection. The journey wasn’t easy, but it was worth it. With each passing day, I would discover something different about textiles and therapy. Gradually, I created textile surfaces based on self-therapeutic procedures and activities. The initial idea was to create an iterative collection with a single silhouette exhibiting these textiles. Later, through the process of making, I realised that I could play with hemlines and their lengths to demonstrate continuity or ‘flow’. The entire collection is devoid of hem finishes to oppose the idea of flow disruption. The result was rather satisfactory.

What part does sustainability play in your design practice?

Sustainability has been very carefully considered in this collection. It has played a major role in redefining my design practice and methodology. The collection is made from discarded and dead stock denim fabrics gathered from the streets of India, where the denim weavers throw away a lot of their fabrics due to minute defects that often go unnoticed. Since the discarded denim was often in bits and pieces, it was difficult to cut out a complete pattern from a single piece of fabric. This changed my approach to the entire design process. I would arrange multiple pieces of discarded denim to fit the area of the pattern after considering shrinkage and fraying. These pieces were then subjected to intensive boiling, heavy washing, harsh sun drying and bleaching. The prepared base denim was then used to create textile surfaces incorporating the principles of rhythm and repetition. The resulting textile pieces were then finally shaped according to the pattern piece. This procedure ensures minimum wastage and maximum utilisation.

What’s next for you?

Moving forward, I want to work in the industry for some time to understand the specific market and the minute technical details of garment making. I also want to work with different textile surfaces in therapeutic setups to implement my research. In the future, I see myself exploring textiles and therapy within a studio set up with actual clients elaborating on their experiences with specific textile making practices. I want to put my research into an actual practice that benefits humanity and fashion.

Find more of Shrinvanti’s work here.