Childbirth, first-time mothers and female labour: An excerpt from Ainslie Hogarth’s new novel, ‘Normal Women’

WORDS BY AINSLIE HOGARTH

“To love something this profoundly. It was no wonder some people were destroyed by it.”

They’d ended up slicing her open, which was great. She was sort of hoping for a C-section. The stories Anya’s friends had shared about their incontinence, their prolapses – one of the women, Ellen, describing the way a hunk of her bladder or vaginal wall (who knows!) would slip down throughout the course of the day. Bulge.

She’d framed it as a minor irritation, easy enough to poke back in, no different from enduring the day with a sock that keeps slipping beneath your heel. Except it was every day. And it was body parts. Very inside ones. Creeping out like some activated fungus. Which was why pretty soon, Ellen explained, casually, hooking an invisible hair from her mouth and tucking it behind her ear, she’d be looking into some sort of scaffolding.

A mesh – interlocking her fingers, miming weight – that would hold it up for her. Like basketballs, piped in Dawn, another one of Anya’s friends who Dani had recently met, in a high school gym equipment room, remember?? Laughing, nodding. Though Ellen, Dawn and Anya had all gone to different high schools, the equipment rooms, with their suspended basketballs and oily, low-frequency stench, were very much the same.

And Ellen, Dawn and Anya had all heard of the mesh too. Because they all knew someone, a woman, secretly held together by it. Dani wrapped her mouth gracelessly around a blast of corn chips and wondered why the fuck no one had told her about the mesh before she got pregnant. “Well, Elaine had a fourth-degree tear,” Anya revealed, thumbing a wayward gob of guacamole back onto her chip.

Anya, in many ways the worst of them, Dani’s oldest friend, who she loved like a sister but also found unkind, judgmental, manipulative, competitive, and actually a bit racist in ways she seemed to perceive as simply good sense: “Immigrants are driving up the cost of living in the top cities, I’m sorry, but it’s true. If you come here from somewhere else you should have to start in, I don’t know, some middle-of-nowhere town that needs the economic push, you know? It’s only fair. And it’s good for everyone.”

Anya had experienced both, a C-section and a vaginal birth, and though the vaginal birth had been amazing, oh my god, it’d also left her with chronic incontinence (Do you know that I piss myself? A little bit? Every goddamn day?) as well as what the doctor referred to as sexual dysfunction, which was so severe her husband, Bill, had taken up yoga.

His back, once a densely knit tapestry of chronic pain, was now limber as a river reed. We should have stopped fucking years ago, he joked, and Anya nodded readily – honestly, though, a hand on Dani’s arm, her tone edged with a conspirator’s sincerity, he’s like a different person.

By almost every metric Anya was a very Normal Woman. At the very least she engaged with the material trappings of their sex in a way that Dani had never been able to – Anya exercised regularly, or at least complained regularly about not exercising enough; she had defined triceps, lean thighs; she monitored her protein intake, and knew the difference between soluble and insoluble fibre.

Anya spent time outside, her chest and shoulders tanned to a fine, freckled hide. Nails always buffed, cuticles repressed, hair a multifaceted illusion of fresh blonds. Her leggings were expensive, their crotches fortified, and she’d always, since high school, had her bikini area waxed professionally, sugared when that was the trend. Eyebrows too. Threaded now. By a woman in the mall who apparently Anya would have preferred to start her life in the prairies.

Dani imagined a small farming community with perfect eyebrows, in stark contrast to the shaggy and wild wheat they sowed. Basically, Anya was the portrait of self-care, a pursuit the mothers in the online mom forums held sacred, and another maternal obligation for all but the lucky few to fail at spectacularly.

Dani wasn’t exactly sure how she and Anya had managed to remain friends for so long other than they both liked drinking too much and had once known, intimately, the versions of one another they hated most: the raw, cruel, earnest material of their youth they’d both taken great pains to pasteurise and recast into forms more consciously selected.

When Dani and Anya were alone with one another, they allowed these former selves to unfurl languorously from their facades, accessing big, true laughs and rare peace, despite having, technically, nothing in common.

“What’s a fourth-degree tear?” Dani had asked at that lunch with the mum friends, the last lunch, she didn’t realise at the time, before she would go into labour. She leaned back in her chair as though distance from the explanation might inoculate her from it. She folded both hands over her moon of living belly, protecting the little person inside too. Nine months pregnant. Almost there.

“A bad rip,” said Ellen, still chewing, clearing away nacho debris with a long pull of unsalted margarita. “Poo hole to goo hole.” She raised her eyebrows. And maybe that’s why the C-section happened. Because Dani had just wanted it so very badly: sweating, panicked, coiled helplessly around every contraction, incapable of just letting go, of breathing, her mind’s eye yoked to Ellen’s salted lips, tight around the vowels: “Poooooo hole to goooooo hole.”

And the body is just such a mysterious thing, especially as it pertains to childbirth. In fact, after reading book after book about the connection between fear and pain, the orgasmic, ecstatic, rapturous birth experience, the power of visualisations – I am petals unfurling, I am huge, I am opening wide as a cave, exactly as I should, for my baby to spill without pain – one might even come to the conclusion that the body is only mysterious as it pertains to childbirth.

That otherwise it’s actually pretty predictable: a system of sphincters and pipes and cables that harmonise chaos like the warming of an orchestra pit, ins-and-outs and organs thumping, processing fuel, petals unfurling, becoming huge, ejecting waste and sometimes life, and that was Lotte, Dani’s precious baby, who mercifully bypassed her vagina, cried only when she really meant it, and completed a truly sublime figure eight when she pressed her face into Dani’s breast to eat.

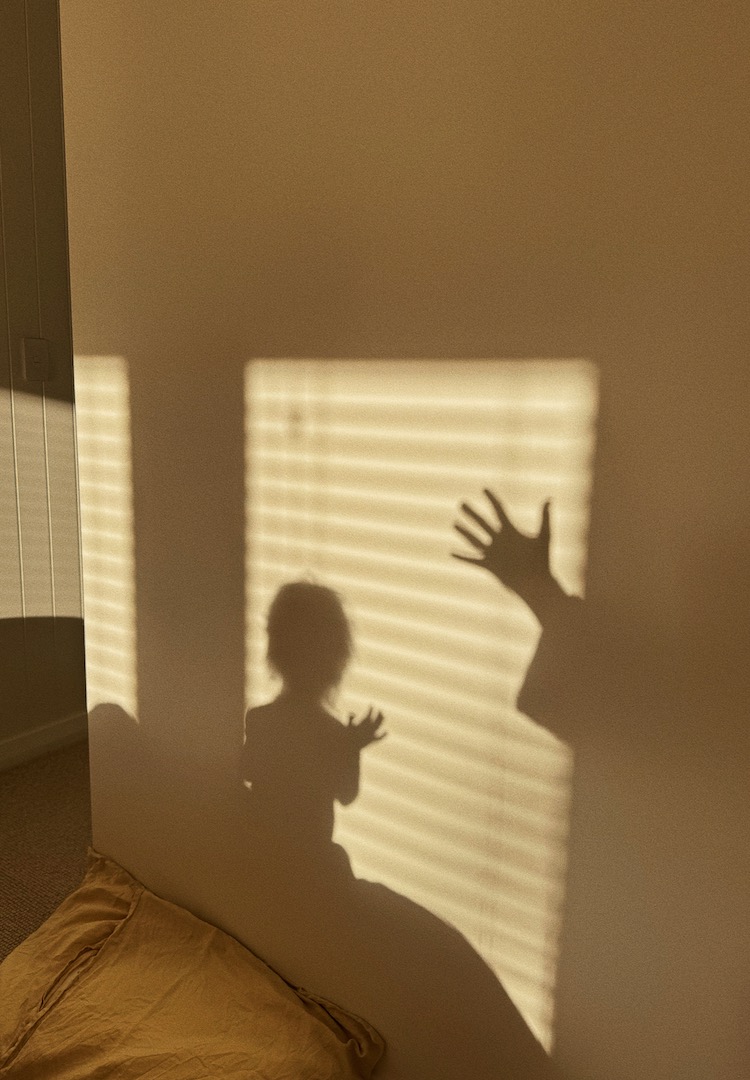

Wide awake in the hospital that first night, Dani’s facade warmed, then thinned, to accommodate her new identity, this new love. And not just for Lotte either. She loved everyone now, every human being, because they’d all been babies once. And she cried from exhaustion but also because everyone was actually so good inside. To love something this profoundly. It was no wonder some people were destroyed by it.

This is an edited extract from Normal Women by Ainslie Hogarth, Allen & Unwin, available to purchase here.