Blueberries’ author Ellena Savage on sharing her private self on the internet

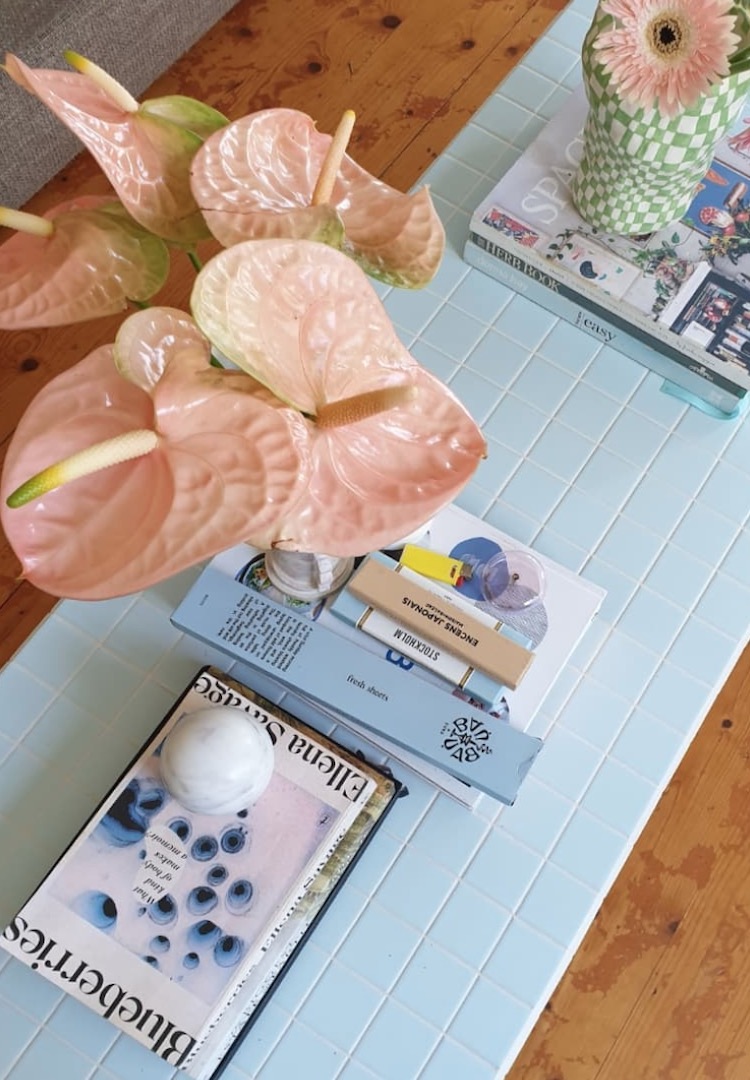

IMAGE VIA @P0LY_DESIGNS/INSTAGRAM

WORDS BY ISABELLE SACKS

“The irony is that I wrote a book about feeling left out and then the book gets published and people start opening doors for you.”

I must be candid; Blueberries might be the reason I’m back in therapy (I was definitely teetering on the edge but blaming an external source is where I’m at right now). When I read Ellena Savage’s first essay collection late last year, I had a brief crisis about the meaninglessness of my job and late-stage capitalism.

I totally withdrew from the guy I was seeing, projecting onto him the offences of men who came before him (sorry dude!) I had to come to terms with the profound mediocrity of my own writing. I forced it on everyone in my life and then dealt with the crippling dread that they’d glean some deep secret about me from the pages.

Looking for some similarly thought-provoking reads? Try our Life vertical.

A book that almost dares you to try and categorise or assign it a genre, Blueberries’ own blurb describes it as a “blend of personal essay, polemic, prose poetry, true-crime journalism and confession.”

It spends time on the streets of Lisbon, in wintery apartments in Berlin and at a very expensive writers’ workshop in America, but Blueberries is aggressively Melbourne (think mentions of the number 19 tram and ratty Brunswick sharehouses). It’s a book about being in your twenties, about womanhood, about being an artist and a writer, about bodies and histories and power.

It’s been a year since this memoir of sorts was published, and on the heels of its nomination for the Stella Prize I wanted to meet Ellena, both to gather her reflections on having it out in the world and to make sure she knew what this book means to me.

I’m speaking to her over Zoom from her place in Athens, backgrounded by the obligatory stuffed bookshelf and her husband Dom shuffling in and out of frame. After requisite chatter about the state of lockdown in our respective locations, I pull out my copy.

It’s covered in a borderline counterproductive number of yellow post-its. She laughs, “I always just presume that anyone who’s read my book has been forced by my old housemate or an ex… like they’ve said, ‘Read it because my friend is really poor, and she needs your money!’”

Given ye olde panoramic, Ellena hasn’t gotten a chance to do all the authory things one does when they release a critically lauded essay collection. No book signings, no writers’ festivals, no interactions with readers who know all about the wristies she gave to her high school boyfriend under a bridge in Coburg North. She deadpans a whole spiel about how COVID-19 has been singularly bad for her (and her alone).

Despite delving deep into sensitive topics – her relationship with feminism and religion, discussions of class and race and queerness and what it means to be an Australian, her experiences of sexual assault and abortion – Ellena bristles at the assertion that there may be any true self-revelation or vulnerability in the book.

It’s not that she didn’t live and feel everything that she wrote, but she does challenge me to consider how the process of pushing sensitive material through the artificial process of literary construction can domesticate it.

She declares that nothing in it is something she would conceal from a friend, though later recounts conversations with friends who’ve expressed feeling like they’d known so little of her after reading it.

“People are dealing with an artifact. It’s not a human being, it’s a book.”

Reflecting on where she was in the early stages of the book’s development, Ellena tells me that she doesn’t even feel like the person who wrote it anymore. 33-year-old Ellena is a married property owner with a PhD. She can get stable work as a teacher. She has won grants and prizes.

27-year-old Ellena was in a state of financial, personal and professional precarity. She was working like a maniac. She was getting rebuffed. She was not connecting with an audience. “I felt like every door was being closed on me and so I wrote that with a kind of anger that I don’t necessarily feel now,” she says.

That’s not to say that she doesn’t stand by what she wrote, more that she doesn’t want to buy into the trend where artists can’t acknowledge that their early work about being marginalised has granted them a certain level of class mobility (Eileen Myles-ing, if you will).

“The irony is that I wrote a book about feeling left out and then the book gets published and people start opening doors for you… I was brainwashed by Marxists when I was 14, so I’m always looking at how things are produced, like how the sausage is made, so I want to be honest about the fact that I’m no longer as broke as I used to be,” Ellena explains.

Truth and honesty come up continuously in Blueberries as in our conversation. We talk about truth’s elusiveness, its subjectivity, its ability to be warped by time and trauma and anything else, its essentialness in good writing and in citizenship.

In the essay ‘Houses’, Ellena describes her early writing as being hampered by an inability to tell the truth, her diary plagued by insincerity and embellishment. “When you’re a teenager, everything is a bit of a lie. Your haircut is a lie. The way that you talk about the person that you have a crush on is a bit of a lie… I think that learning to tell the truth is a way of growing up.

“If you continue to lie to yourself, you can’t really be responsible for anything,” she tells me. Now, her commitment to truth is a self-described character flaw. She struggles to tell anything greater than a white lie. She says that people find her blunt.

But is the truth actually articulable? Ellena seems to be in many minds, writing that the idea that it could be is the “biggest lie told by and about writers”. She tells me that making herself “appear not perfect in order to tell the truth is important”, that she sees it as “a form of citizenship” while couching it in anecdotes about her use of persona in storytelling. “Living successfully requires some degree of acting,” she says.

Maybe that’s about self-preservation. Writing is inexorably linked to her identity, but it’s also a job. It’s an occupation that requires commitment and time and continuous learning. It’s a profession met by her insatiable drive to “catch up”, to overcome her perceived lack of natural talent.

Ellena thinks this attitude may have stemmed from her mother, a musician who taught her you cannot fake your instruments.

“I was kind of raised with this idea that art-making is not a whimsical gift from the gods. It’s a daily practice.”

She’s written serious essays about human rights, she’s written sexy poetry, she’s written “bad” short fiction and PR fluff. She’s been published everywhere from The Paris Review Daily and the Sydney Review of Books to the Guardian Weekend and Eureka Street. She’s edited The Lifted Brow. She’s taught at RMIT and the University of Melbourne.

Much of the book revolves around writing as work, and Ellena doesn’t pretend to make it look effortless. In ‘Allen Ginsburg’ she writes about going to war with editors over her unorthodox use of grammar, a battle she clearly won.

Blueberries is delightfully experiential, challenging readers to abandon their expectations of the English language and treating them to a masterclass in playing with form. There’s no doubt she’s earned the right to fight for sentences, but she stresses that she couldn’t have done so if she had gotten the book deal any earlier.

“I can see so many mistakes in it as well, but I’m not ashamed of them or embarrassed by them. That’s the essay of the writer that I was then, and she’s doing something interesting and she’s doing something well, but I would write a very different essay now.”

Part of her ability to push the boundaries has also been about finding people in the literary world who understand and value the work that she’s doing, even if working with her results in a technical financial loss.

She credits British-Israeli chef Otam Ottolenghi for essentially subsidising her career. Her literary agency Lutyens & Rubinstein also represent the wildly popular cookbook author, whose books have sold over 400,000 copies in Australia alone.

I’d push back on her characterisation there and note the somewhat remarkable success that the book has had, especially considering Australia’s lack of established literary tradition when it comes to work like hers – it’s no coincidence that reviewers struggle to compare Ellena to Australian writers other than her mentor Maria Tumarkin.

The Stella Prize, a major literary award celebrating Australian women’s writing, is just the most recent accolade in Blueberries’ glittery season on the awards circuit. It’s been short and longlisted for the Victorian Premier’s Literary Award, the Penguin Random House Australia Literary Prize, the Scribe Nonfiction Prize and the Kill Your Darlings Unpublished Manuscript Prize.

Ellena’s eyes crinkle at the edges, she looks up, she shakes her head. “You certainly don’t write a book like Blueberries presuming that it’s going to get on award lists. It’s a pretty strange book.”

For her next project, Ellena is tackling a novel, an endeavour she’s finding exciting and rather enjoyable. I wonder what’s sparking her interest at the moment, why she’s writing. “I think if I could summarise that, I wouldn’t have to write a book about it,” she laughs and turns the question back on me. Cue a second Ellena Savage induced existential crisis.

Blueberries (2020) is published by Text Publishing in Australia. It can be purchased wherever fine books are sold. You can keep up with Ellena here.