How growing up mixed-race defined my relationship with beauty

WORDS BY ASHEDA WEEKES

“Being Australian and Malaysian-Chinese has fed so much contradiction around what is to be a woman, and how to look like one.”

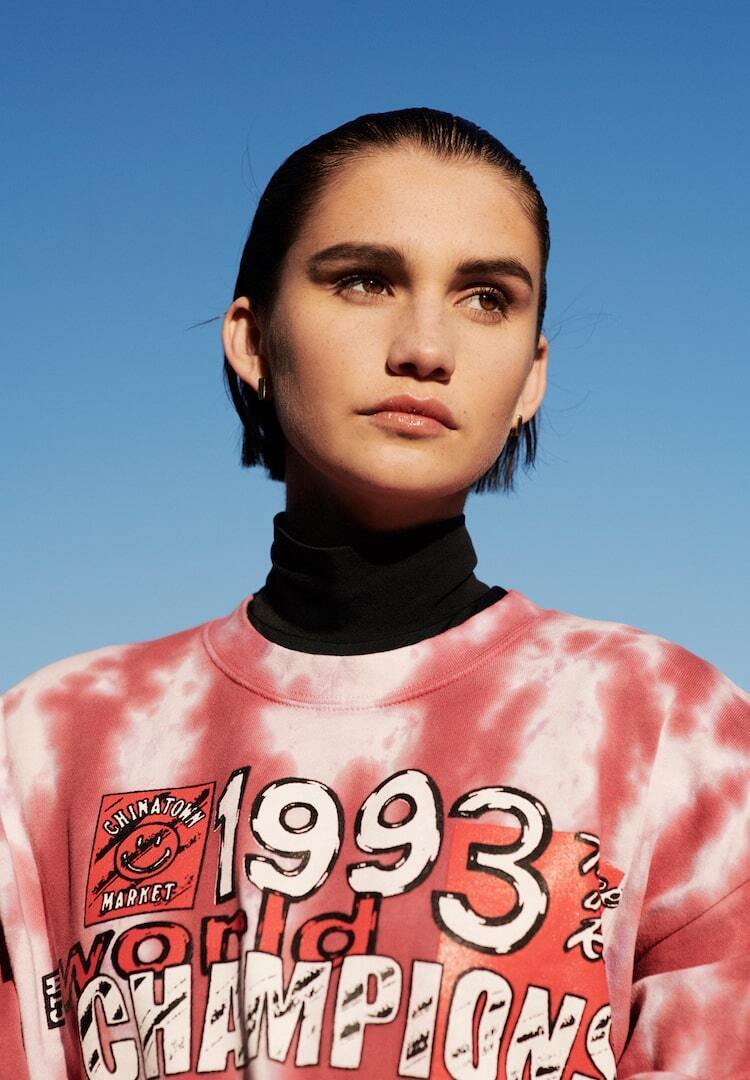

For International Women’s Day, Converse launched its My Story collection, a female-designed reimagining of the classic Chucks. Inspired by fearless, bold and independent womxn, My Story helps give you the words and colours to tell your own story. To celebrate this release, we’ve given Fashion Journal readers the opportunity to have their own story published in our pages. Here, Asheda Weekes unpacks her Australian and Malaysian-Chinese heritage and the part it’s played in her journey of gender and beauty.

Whenever we’re at my mother’s family home in Kuching, Malaysia, she will still avoid the sunlight because my Neknek (grandmother) tells her she’s “too brown” – even after 54 years. Born as a Malaysian-Chinese, Muslim woman with Indigenous Melanau roots, I was faced with the same cultural collision that informed my mother’s gender and beauty identity.

As part of a long-winded list of rules found in these societal conventions, my mother Suze was always told to wear conservative clothing, not put on a lot (if any) makeup, and to be as fair as possible. Seeing the impact it still has on her, I’m left realising how much it’s defined my identity too.

Looking for some similarly thought-provoking reads? Subscribe here and we’ll send them straight to your inbox.

Being Australian and Malaysian-Chinese has fed so much contradiction around what is to be a woman, and how to look like one. When I was born, I was described as a “china doll”. I had fair skin with black-brown eyes and hair. I was glorified for my innocent, porcelain features and mixed skin.

Back home in the Australian summers, I would play in the waves and lie on the sand. I started getting freckles and developed an olive tone. Even as a tween, being tanned was a good thing. Any opportunity to be out in the sun was met with comments from friends saying, “I can’t wait to get more tanned.” So, if I was looking a little fair, I always worried that I looked sickly. I would win and lose all at once, depending on where I was at the time.

I hated my freckles back then, too (a byproduct of my internalised glorification of fair skin from infancy). I didn’t want marks on my face. I wanted clear skin. I wanted to be that delicate china doll. Simultaneously, I still wanted the compliments of, “gosh, you’re looking so glowy and so healthy” after a beach trip. I wanted the tan, but all I got was freckles. After learning that laser removal procedures exist, I asked my mum countless times if I could remove my own.

Sadly, it was more than just the freckles that agitated my ideology of being a beautiful girl, and then, a woman. At 13, I had already passed the peak of my adolescent transition – I was 5’9 and towering over my friends. Also, I was living in Singapore where the average height was 5’4. I felt like a giant.

In South-East Asian culture, being petite was beautiful. Even my Neknek said I was besar (big). And sure, she meant well by making a comment about my height, but the memory – now embedded as a nuanced trauma – has made me carry an aching desire to always be small.

The duopoly of internalised racism from both cultures has fed into a complex shame around my identity, gender and beauty. These two colliding cultures somehow fed racism, misogyny and beauty norms in their own irreconcilable ways, but boosted one another too. It wasn’t just how to be a (good) woman, but also how to be a good daughter, and eventually, how to be a wife.

For decades, my mother’s position in the world has been the subject of critique from both her parents and the culture in which she was raised. Her response has been fiery, independent strife. It has been admirable to watch, but I know it still daunts my mother that she’s expected to align with such conventions. She’s been instrumental in helping me overcome my own tendency to fall into these traps of seeking approval.

It’s only been through the last decade of therapy, to help manage my anxiety and Borderline Personality Disorder, that I’ve realised how much gender and beauty play a huge role in my identity.

You’ll see my freckles even if I have some makeup on. I love them – I don’t feel like myself without them being seen. The tone of my skin isn’t a focal point either. As for the rest of my insecurities, it’s been about learning how they’ve amplified my anxiety and subsequently, unlearning these false truths. It’s doing cathartic work such as writing a story like this. It’s about following others on social media and having these conversations, and even having important chats with Suze. I try not to be fixated on what I don’t have and to instead, make space for embracing what I’ve got.

View Converse’s My Story range here.