Is it really so bad to feel incomplete without a partner?

WORDS BY ANNA RICHARDS

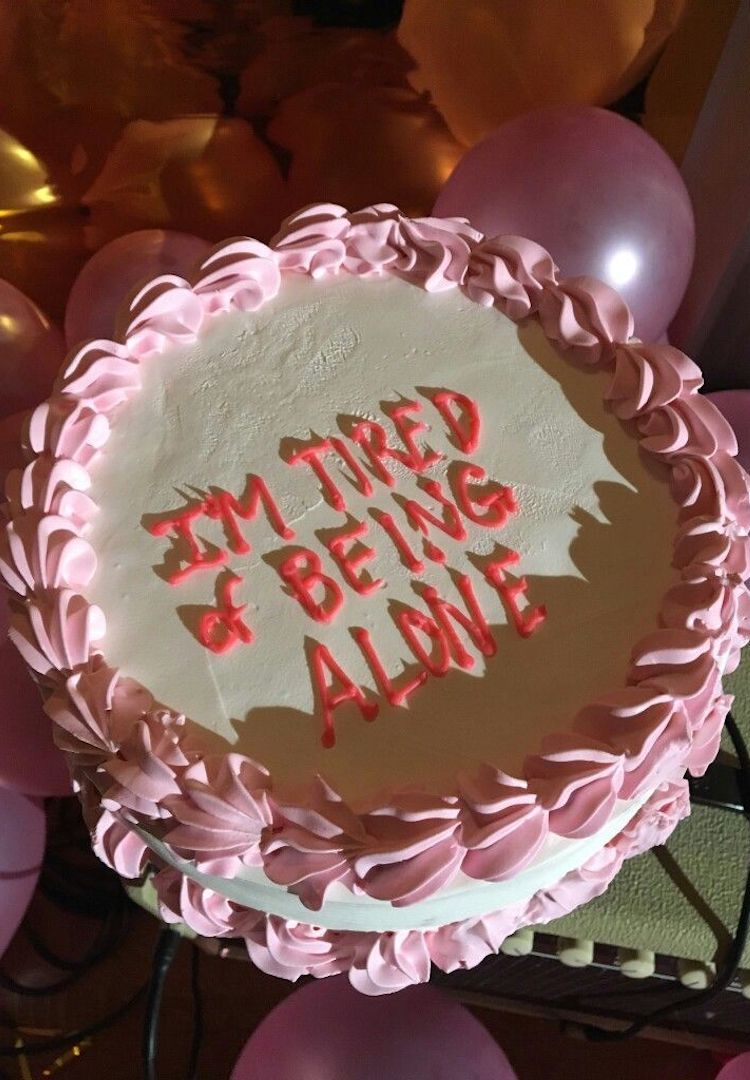

It’s okay to crave company.

Our modern view of the single status is intrinsically linked to growth. After my first proper heartbreak, a friend’s mum soothed me with the following advice: that a broken heart is just as formative as falling in love; that to know yourself you need to learn how to be on your own.

Even further than growth, being able to be alone is seen as a form of strength, and (somewhat ironically) as an attractive quality for prospective partners. Especially for women, the word independent (‘free from outside control; not subject to another’s authority’) is synonymous with not being in a relationship.

We can’t give you a tissue for your relationship woes, but we can help you get your mind off things. Head to our Life section for more advice.

The importance of spending time unpartnered is a fairly recent phenomenon. During the 2nd century BC, the union of two people was viewed as so necessary to the success of society that fragile emotions like love weren’t part of the marital consideration.

Then later on in the Enlightenment period of the 17th and 18th centuries, the pursuit of happiness was prioritised and love was seen as integral to that, and for the first time unions were encouraged because of how they made us feel, not just for cementing status and wealth.

By 1970, after centuries of inequality for the wife, “marriage law had become gender-neutral in Western democracy”, and the decision of being alone or in a relationship was up to the individual.

The Australian Institute of Family Studies predicts that by 2026 single-person households will outnumber family households. That statistic is a powerful reflection of our liberation, both economically and culturally.

It’s also perhaps a reflection of our current milieu, where singledom is encouraged as a path to self-worth. There’s a reason ‘I need to work on myself’ is routinely (and predictably) used in breakups.

View this post on Instagram

Pre this latest lockdown I was at a bar with a friend. It was a cold May night in Melbourne and while we drank we talked about her boyfriend and how I’d been going after mine had moved back to the UK during the first COVID wave. I said that I was happy and that it felt empowering to look forward to going to bed alone every night.

She responded, “Yeah, but that whole thing is so forced onto us. It’s okay to admit that you’re lonely.” Was I just iterating the approved attitude? Stylised Instagram posts abound that tell us you are all that you need.

A New Yorker cartoon that shows a woman on her laptop in bed thinking about the exact same scenario she’s in but with a partner beside her proved divisive in the comments section.

Opinions ranged from “Normalise being single….” and “No, that extra space is for my vibrator” to “Could not love this more”. Someone even expressed that “This sort of thinking is the problem with America today”.

View this post on Instagram

Why is it that wanting love is seen in a negative light? Can it be okay to think of ourselves as happier when we’re with someone? During Melbourne’s longest lockdown last year, an archaic idolisation of traditional unions came to the surface, making many single people question whether they would be happier if there were a significant other in their lives.

Only those with intimate partners could visit each other, and the notion that a designated best friend can’t be just as integral to your mental wellbeing highlighted a new consequence of your relationship status. Unsurprisingly then, dating app sign-ups exploded.

My watershed moment happened during the announcement that our six-week lockdown was only the beginning. I needed to speak to someone outside of my immediate world, and virtual dating was the only possible solution (however cringe some of the Hinge answers may have been).

What were all of those new sign-ups seeking? Companionship? Someone to have different kinds of conversations with? Or possibly stability, something that had felt unfashionable until recently.

It feels like these ‘situationships’ provide all of the above, but especially the latter. Take away our other preoccupations – our social lives and demanding schedules – and having an ‘other half ’ suddenly seems like an important part of fulfilment.

So for those of us with this decision to make, what do we do about that aforementioned growth? Being ‘ready’ for a relationship has for a long time meant having learnt to love yourself, understanding who you are, and being content with an empty bed.

But maybe we shouldn’t be putting so much pressure on ourselves. Maybe self-worth and self-growth can also occur during a relationship. Maybe we know that we’re ready as soon as we want it.

Looking for more on this topic? Try this.