The Mary Quant fashion exhibition has landed in Australia, here’s why you should care

Words by Felicity Pitt

The designer who pulled Australian fashion away from conservative norms.

Mary Quant might not currently be a household name to generations below baby boomers in Australia, but that is set to change. Mary Quant: Fashion Revolutionary is the latest fashion retrospective to open at Bendigo Art Gallery, another landing from London’s Victoria & Albert Museum. The retrospective magnificently captures Quant’s innovative designs and business model, which together exemplify the chaotic pace of the swinging sixties, and changed the way fashion was made, marketed and sold globally.

But beyond the scope of the showcase is the notable influence that Mary Quant had upon several young Australian fashion designers, whose work helped put Melbourne on the fashion map.

Fashion exhibitions right up your alley? Find a few more now showing across Australia right here.

So, who exactly is Mary Quant?

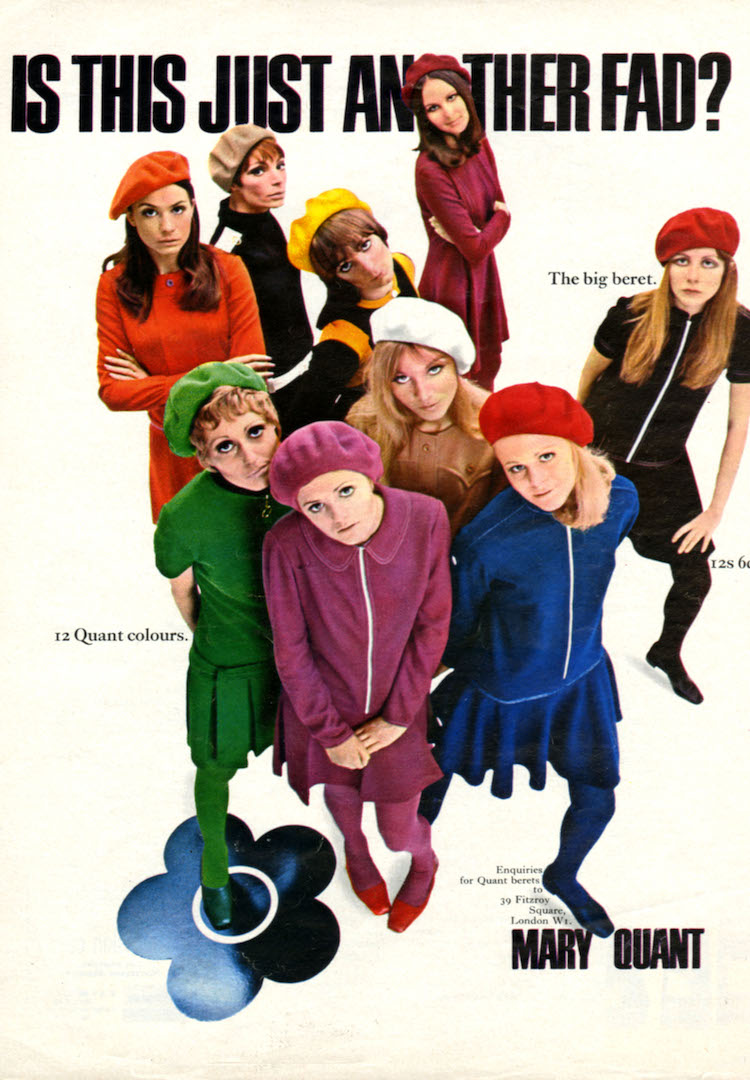

Best known internationally for popularising the mini skirt, Quant spearheaded the British fashion revolution. Her easily wearable designs were bright, witty and – perhaps most importantly – affordable. Keeping pace with the youth-led anti-establishment movement, Quant’s designs disrupted the cinched-waist ideal of 1950s femininity, instead trading it in for a streamlined look that teetered between ‘hyper-girlish’ and ‘office jock’.

Starting small in 1955 with the opening of her first boutique, Bazaar, on Kings Road in Chelsea, demand for Quant quickly grew. By 1961 the Mary Quant clothing range was being mass-manufactured in the UK and she had broken into the US market, striking up a licensing deal with the mega-retailer, J.C. Penney.

The Mary Quant brand took off and shook the fashion world. It helped that Mary was a queen of product innovation and diversification – her devotees needed only to spot her iconic daisy logo to purchase the Mary Quant look, from glitter tights to false eyelashes – as well as the ultimate embodiment of her brand’s rebel aesthetic.

Her business partner, Archie McNair, and marketing-savvy husband, Alexander Plunket Greene, further helped Mary leverage her flair and catapult her work onto the global stage.

Coming to Australia

Britain’s revolutionary waves, however, were slow to reach Australia’s shores. Societal norms were exceptionally conservative by today’s standards. For an example of what magazine content Down Under looked like on the cusp of the sixties, look no further than Teenagers’ Weekly, The Australian Women’s Weekly’s supplement, which published a quiz where readers had to ‘match the secretary to their bosses’.

The judging was based on pictures and choice quotes that explained why each secretary was hired – my personal favourite: “He hired her because she looked beautiful and looked like she could type”.

As well as reading the likes of Teenagers’ Weekly, young women were largely expected to dress in copies of their mother’s clothes, albeit made with different fabrics or trims. By the early sixties, this concept was beginning to be challenged, led by the emergence of a fresh group of young Australian designers who brought the Mod look home.

Of these, there are three women in particular that stand out: Norma Tullo, Noeleen King and Prue Acton. As well as becoming international successes, all designers were frequently compared to Quant.

Mary’s influence on our local designers

Opening a small shop in Melbourne’s old Metropole Arcade in 1956, Norma Tullo, then aged in her mid-twenties, went on to dominate the local ready-to-wear scene. Although she dismissed the Mod look as “scruffy”, Tullo had a flair for adapting the style for a more conservative – yet still youthful – market, never hemming too far above the knee.

Expanding into the US teenager market, she began designing a ‘youth’ range for Butterick Patterns, but her breakthrough success came in 1964 when she struck a multimillion-dollar licensing deal with the Japanese department store, Isetan. It was the first time a Japanese store had ever purchased an entire foreign-designed collection to manufacture locally.

That same year, Noeleen King secured the exclusive licensing rights to manufacture Mary Quant designs in Australia. Born in Ireland, King migrated to Australia in the mid-1950s and became known for her ‘Medieval Mod’ look that captured the attention of Quant. Frequently sharing advertising spreads with one other, King’s designs complemented rather than competed with Quant’s, making her a natural choice to take on the licence. The deal was big news locally, where Mary Quant was still considered a ‘way out’ designer by the media.

A key turning point came in 1965 when British model, Jean Shrimpton, then the world’s highest-paid model, made a sponsored appearance at the Derby Day races and shocked the crowds by wearing a shift dress cut 10cm above the knee, without stockings, hat or gloves. The tut-tutting she received in our national papers became a global embarrassment as the British press came swiftly to Shrimpton’s defence, mocking Australia’s ‘fuddy-duddy’ fashion tastes.

Although Shrimpton’s dress was not designed by Mary Quant, so strong was the popular association between Quant and the style that the debacle pushed wounded local journalists into a somewhat frenzied attempt to promote ‘with-it’ Australian designers, and set them on a quest to discover ‘Australia’s Mary Quant’.

The woman who most attracted this title was Prue Acton. Aged 19 and straight out of RMIT, Acton had started her eponymous label from a tiny studio on Flinders Lane in 1963. Though immediately popular, serious success came in 1966, when Acton became the first Australian designer to secure a licensing deal with the USA – and did so by delivering a collection already released in Australia, that American clientele would have to pay twice the price for.

Acton’s early designs kept pace with many of the popular trends of the sixties: Peter Pan collars, jersey shift dresses and double-breasted pantsuits, but this deal put her ahead of the game. The frequent comparisons to Mary Quant were not based solely on breaking the US market – or the fact that both brands had daisy logos. Acton, like Quant was also a photogenic personification of her brand. She used this marketing tool wisely. Acton also followed Quant’s 1966 advance into cosmetics with her own make-up range, released in 1969.

Acton, Tullo and King also all mirrored the scale and speed of Mary Quant’s immense design output, each producing multiple collections per year for Australia and their international licensees. Harnessing the spirit and energy of the revolutionary times, these female-led fashion houses remain celebrated, though oft overlooked, local examples of how Mary Quant’s model for success resonated in Australia.

‘Mary Quant: Fashion Revolutionary’ is showing at Bendigo Art Gallery until July 11. Purchase tickets here.