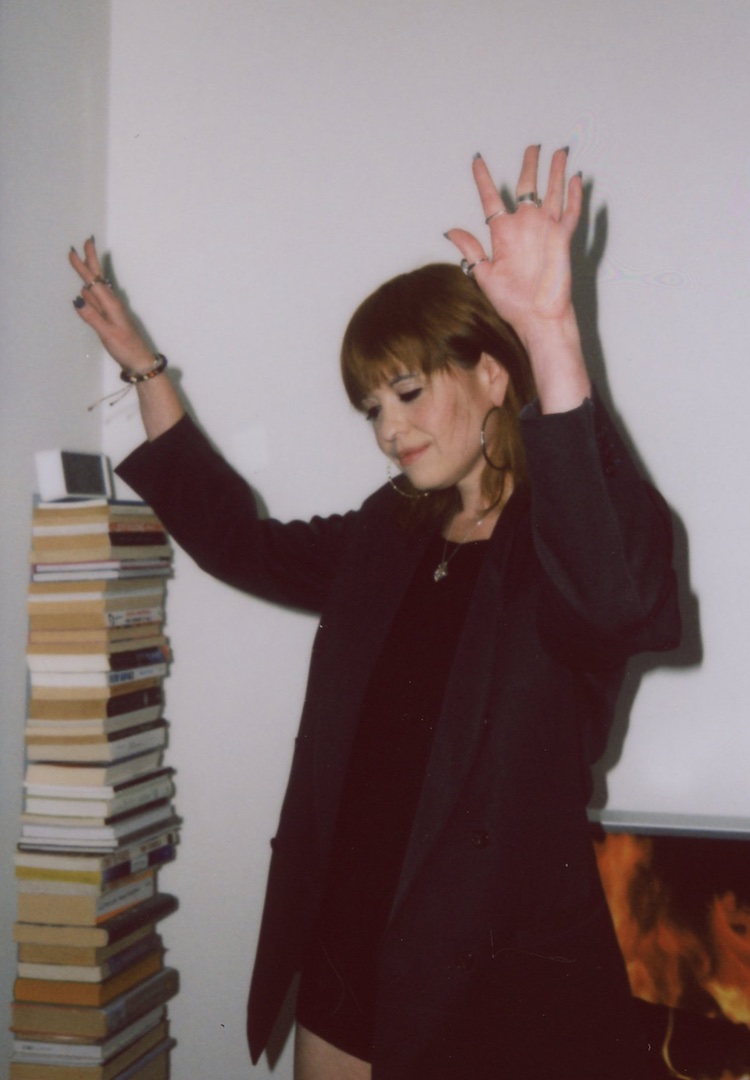

An excerpt from Melbourne writer Ronnie Scott’s forthcoming book, ‘Shirley’

WORDS BY RONNIE SCOTT

“In the end, it was the smoke that did it. I did what people in smoke do. I walked through the door that was opening, and I did it without really thinking.”

Somewhere in the world, two things are always happening: an image of my mother is flashing through someone’s mind, and an enormous growth system is burning. But I had never experienced anything like the smoke in the air that night. I just had never experienced it. In the Uber, with a cold pot of soup on my lap, I was very silent, and David was very silent, and in the front of the car the driver was silent too.

When we passed Darling Gardens the smoke looked soft and beautiful, as if it had been pushed gently up from underneath the trees. When we exited the car in front of the apartment block, we walked quickly through the gate and through the parking court and towards the stairs that led up to my apartment. We ducked low, like we were caught in rain and not in burning country, and as if ducking bushfire smoke saves you from the smell. I don’t know what I thought would happen when we got upstairs.

Interested to hear how others navigate the world? Head to our Life section.

I don’t remember if I thought we’d finally discuss the thing we’d determinedly not spoken about since he’d come back from the music festival, those few weeks ago. I’m sure dreading what would come next played a part in our stopping at the bottom of the stairs, even with the smoke. The main reason, however, was the startling sight.

There were four apartments in the block; I know they don’t make four- or six-bedroom apartment blocks anymore, but there are several like it, squat, brick buildings from the seventies that break up the clots of workers’ cottages between Wellington and Hoddle. The one-bedroom I’d bought was small, but in a pretty spot; it was on the top floor, with its own front stairs and wraparound landing, which was partway hidden by plane trees as it winked out at the street.

Since I’d bought into the building, it seemed like every old apartment in Collingwood had been flipped and sold, or sold and kept ugly; in September, it was the turn of the apartment under mine, a two-bedroom that turned out its quiet, delivery-driving students and after being briefly advertised was sold prior to auction.

When spring turned to summer, tradies began showing up as I left for work. They plied their unseen trades in the apartment, leaving clue-addled piles of debris in the parking court. Just after Christmas, the old roller blind over the sliding glass door of the apartment, reliably see-through and revealing of shadowy humanoids, had been replaced by a clean, charcoal-coloured scrim that seemed to have been cut flush into the sliding-door frame.

Since then, the apartment’s occupants had been presumed but unproved, substantiated only by the carapace of a Land Cruiser that had materialised in the parking court and then not moved. And now here they were, with the scrim up and all the lights on, a woman and a man peering out from behind the sliding glass door, each of them holding an empty wine glass.

The woman was barefoot and obviously pregnant, relaxed in the shoulders, poised in the hips. She had a wide face, shining white skin and a neat, jagged haircut. She was wearing a shift dress in a deep grey, stretchy fabric.

The man was tall, also white but I thought quite tanned for Melbourne, certainly younger than the woman and perhaps the same age as me. He had the blocky chin of the classically handsome, but the slightly sweaty features of the slightly green. He was wearing jeans, black socks and an untucked, blue-purple dress shirt. When the woman waved excitedly and held up her glass, he stood back.

She pointed at the glass and then pointed at me, and then she pointed at David. She slid open the door a little. “I’m not pointing at the smoke,” she said. “I’m pointing at you! Come in for a drink!”. The door slid closed again. “That’s my boss,” said David. I looked at him, questioning. “I’m not even kidding, that’s my boss,” he said. “I don’t want to have a drink with my boss on New Year’s Eve.”

David was in his mid-twenties, but it was hard to tell, because whereas I’d had rather adult-ish features since I was a girl, he was one of those men who would probably always look as though he’d either just woken up or just been born. I’d met him at a house party three and a half years earlier, and since then David had been working front-of-house in a bubble of mid-tier bistros in the loose triangle between Collingwood, Preston and Coburg.

Before I’d bought my apartment, when I still lived at Shirley, the two of us had a sleepover one night during the week and one on weekends, ideally a Friday or a Saturday but just as often a Sunday, depending on when he was rostered on for a shift. The setup had always worked extremely well for me, and we’d kept it up even after I’d bought my apartment. He’d stayed at his sharehouse in West Brunswick. We had a nice, comprehensible routine.

For this reason, I’d been wary in the middle of last spring when he’d made the surprising decision – it was presented as a surprise – to move into the apartment behind mine. It was on the top floor of the building, another one-bedroom that had then come up for rent, and which was accessible by its own set of rear stairs. A ‘big life move’ was out of character for David, and it had taken all of the spring and into the summer for me to relax into the reality of his having moved in. To my pleasure, it had not changed our routine one bit; we still valued our time together, and each valued our privacies. David was happier for having moved out of the sharehouse, and otherwise, our lives were largely as they had been.

An exception was that, because he now lived in a one-bedroom apartment in the inner city and not with a rolling succession of students and baristas and touring musicians who’d nevertheless split the bills, he’d begun working daytime shifts as a cash-in-hand gofer in a nondescript warehouse just east of Smith Street, packing and delivering its whipped, fermented, vegan condiments.

Since then I’d heard quite a bit about the boss at the factory, the famous condiment maven, Franklin ‘Frankie’ Morrison, and not only because I was the daughter of a woman who was a well-known food personality herself. I had no doubt Frankie was the boss who was now walking away from the sliding glass door in the downstairs apartment, towards the gleaming white benchtop in the new open-plan kitchen and setting down her and the man’s empty glasses.

Along with her famous work friend, Abi Zhong – their names were always spoken together, and always in full – Frankie Morrison worked in an office high above the warehouse floor. I pictured it as a foreman’s office, from which, so alleged David, she blitzed into meetings, gave fast opinions that invariably lengthened others’ days, and then went out with Abi, to Smith Street, for sandwiches.

I had never taken the complaints of this dynamic seriously, being myself a boss, and being not unfamiliar with the mentalities of assistants, who had populated my mother’s house when I was growing up, and who had not been without their difficulties. But it still wasn’t inevitable that we were going to go into Frankie’s apartment, not even as she opened a cupboard and retrieved two fresh glasses; not even when the man returned to the sliding glass door, unfolded his hands from where they rested quietly behind his back, and began to slide the door open.

I may have thought I knew better than David – and sometimes I truly did – but I also knew he trusted me, and I liked looking out for him, and I believed it when he repeated his preference: “I don’t want to go in there.” In the end, it was the smoke that did it. I did what people in smoke do. I walked through the door that was opening, and I did it without really thinking. I knew without looking that David would follow me.

This is an edited extract from Shirley by Ronnie Scott (Penguin Random House, $32.99), available February 7. You can pre-order a copy here.