How my grandmother taught me to dress well and feel beautiful

Words by Indah Dwyer

An ode to Puska – fiery tomboy, trend psychic and Chanel lover.

Whenever people question me about my clear skin I tell them it’s my Eastern European heritage. I do this because it’s more interesting than saying it’s my morning routine, and I’m all for paying tribute to my skin’s humble origins.

Sometimes this answer paves the way for a follow-up statement about my ‘unique look’, which I try to take as a compliment instead of letting it trigger unwarranted self-analysis. “I come from a long list of unique woman,” I replied recently. Even though my response was lighthearted, the weight of its truth hit my stomach’s floor.

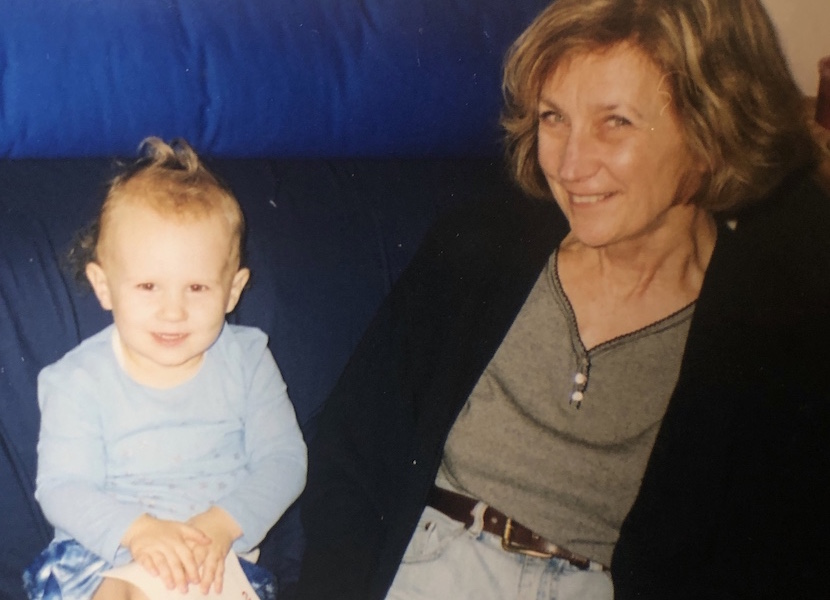

A unique woman whose name is highlighted on that theoretical list is my grandmother, Puska — one of my closest friends and a vessel through which I have always defined my idea of beauty.

She was born Eugenia Tuma in Hanover, Germany on the 26th of September 1940. Puska came into the world during a period of European History that was disturbing, to say the least. A grim series of events left her and her mother — my great grandmother Xenia Tuma — each prioritising their chances of survival alone. The pair separated three times over the years but, thanks presumably to divine fate, always came back to each other. When Xenia escaped from prison after being suspected as a spy, she found Puska in an orphanage and fled Europe on a boat destined (unknown to them) for Sydney.

I was told the night after Xenia retrieved Puska from the orphanage, it was bombed. I’ve never really been one to believe in destiny, but in this case I’m willing to surrender to the idea.

As a child, I tried to get as close as possible to Puska’s past so I could know her better. I would inspect her hands as they went about their daily tasks like squeezing oranges or applying moisturiser. They were hard-working hands, boney and veiny. But they were also so elegant, manicured and embellished with rings of sapphires.

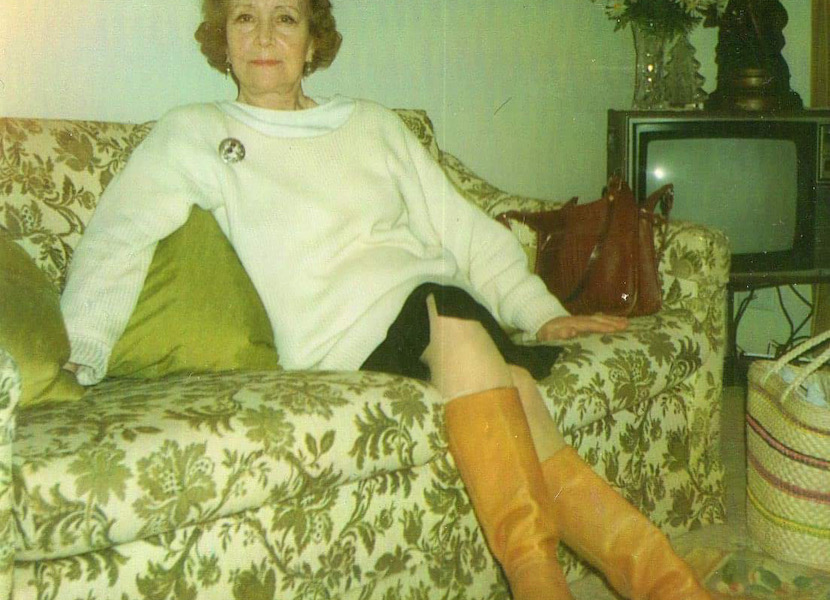

Puska was first and foremost a tomboy with a fiery demeanour. She’d tell me how she had been kicked out of eight schools before she was a teenager. “I couldn’t be tamed!” she’d laugh, “No one was going to tell me what to do and what to wear.” Even in her later years she projected this boldness.

When I was a girl on the threshold of womanhood, I wasn’t happy about it. I felt like I was being robbed of the ease that came with being in my child body. Bodily changes were new inconveniences I hadn’t come to accept, but I could usually find solace in Puska.

We would talk about beauty standards, and she’d introduce me to different kinds of literature. I began to reject how society viewed young women and felt empowered by my self-awareness. She’d tell me her experiences with her own body and her gender, to show me all the different ways a woman can evolve.

When I started wearing makeup and better outfits, Puska noticed. My birthday and Christmas presents suddenly came in a white box with the Chanel ribbon tied around it. She treasured Chanel and everything French – her makeup cabinets and eyelashes coated in blue Chanel mascara testifying to her devotion. But I think Coco Chanel’s journey from rags to riches held a place in her heart that ran deeper than the brand’s luxurious status. It symbolised a rise to power in a time where ‘powerful’ wasn’t something the world gave women a chance to be.

Puska would call me to talk about the pieces she saw on the runway each season. But the conversation was never to make observations about a designer’s newest collection. The point of her call was to share her divine intuition that it would all come back into fashion.

“I don’t give a rats, really darling,” she would say. “But I just knew the trends would come back. I didn’t throw any my old clothes out and I’ve have made up a bag of them for you.”

My family joked that she just needed to get rid of her old clothes, but the way Puska spoke about these garments made it sound like what I was receiving outdid anything on the runway. I’d try on her old clothes while she’d sit on my bed with a gin and tonic in hand. She’d bob her barefoot painted toenails up and down, playing with her short blonde hair and asking me about anything from movies to men. The clothes that did fit on my tall figure she’d stop and smile at. She always looked like she was admiring her reflection in a mirror.

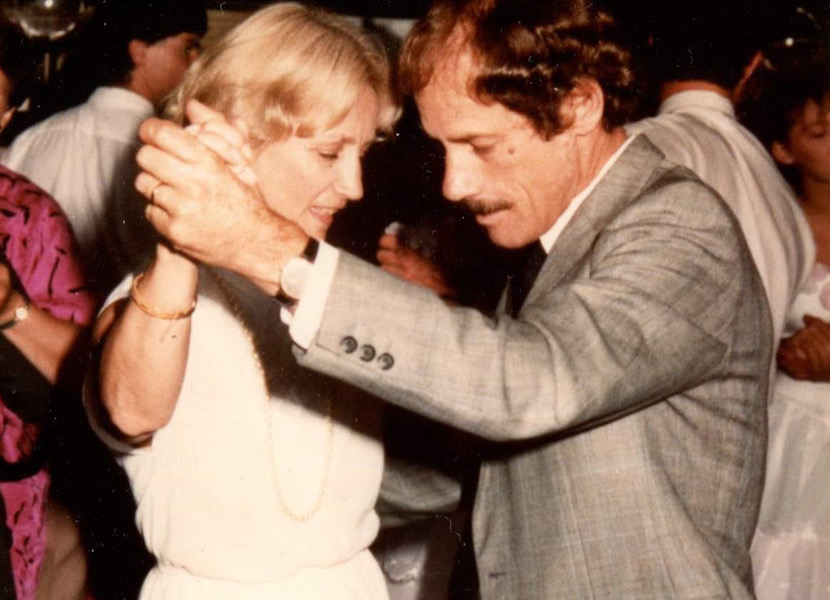

When she passed away last year, it just didn’t make sense. She was a force that never stopped moving; always the last on the dance floor.

Before the funeral, I got ready in front of her big mirror in a nostalgic, blue-tiled bathroom. I remember doing things you do when you feel disconnected from your body. I lifted my chin, put my back straight and turned my head to the side. I felt so made up of other people, so familiar but also so foreign, an ever-changing body.

Regardless of my numb insides, I still managed to prepare an outfit that I felt strong in. I wore a white fur coat from Paris — duh — with emerald drop earrings that were not at all discreet, and a long, spaghetti strap velvet dress that probably wasn’t either. Sitting in the first row, I looked behind me and saw a sea of people wearing waves of colour.

Even on the saddest day of my life I felt beautiful. That’s the philosophy Puska lived and breathed; despite not having beautiful stuff happen around you all the time, you can fill yourself with knowledge and beauty and find ways to bring the good things back again.

I learnt from her example that we are all capable of renewing ourselves. Clothing and makeup can be the vessel through which we can create traditions and invent our own legends.

What my family and I experienced so closely was an honest woman who was ahead of us in life, full of wonderful words, humour, ambition and good taste. It equipped us with the weapon of a powerful woman before we even knew that was something we needed.

Once Puska pulled me close and told me that beauty is all about attitude. I know that despite life’s challenges, her beauty was a triumph.

And I carry it with me always.